New Feature: TINTYPE TUESDAYS!! Fun Classic Movie Pix for That In-Between Day

We all have our little tricks to get through Monday, and Wednesday is Hump Day, and by Thursday we can see the weekend peering over the hill… but what of Tuesday? To throw a little love to the neglected almost-middle child of the week—which we’re supposed to muddle through without, well, anything—Sister Celluloid is launching a new feature, TINTYPE TUESDAYS, where we’ll post some fun classic movie pix every week!

And we’re kicking things off with… Great Moments in Lady Chin Dimples! Starring (so far) Elsa Lanchester, Janet Gaynor, Sophia Loren, Ava Gardner and Jean Harlow…

Please do add your favorite cleft-chinned classic actress in Comments; I know there are tons more out there, but I wanted to get this party started!

By the way, this is the second new feature in a month; earlier we launched STREAMING SATURDAYS, bringing you a fabulous free movie every weekend! You can check that out here!

And be sure to check back next week for another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAYS!

Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant: An “Indiscreet” Friendship

“A kiss could last three seconds. We just kissed each other and talked, leaned away and kissed each other again. Then the telephone came between us, then we moved to the other side of the telephone. So it was a kiss which opened and closed; but the censors couldn’t and didn’t cut the scene because we never at any one point kissed for more than three seconds. We did other things: we nibbled on each other’s ears, and kissed a cheek, so that it looked endless, and became sensational in Hollywood.” —Ingrid Bergman, recalling The Kiss That Launched A Thousand Antacids in the Hays Office.

In a way, that Notorious kiss mirrored Bergman’s lifelong friendship with Cary Grant: an effortless intimacy, never really separated even when apart—and always finding their way back to each other.

They first met briefly in 1938, at a party David O. Selznick threw to welcome Bergman to Hollywood and promote Intermezzo. But they didn’t spend any real time together until Alfred Hitchcock teamed them up eight years later. Bergman had just painfully parted from war photographer Robert Capa, whom she’d met and fallen in love with while entertaining the troops in Europe. Grant was in the midst of a divorce from heiress Barbara Hutton. Orphans of the storm, they found safe harbor with each other.

Usually friendly but reserved toward his co-stars, Grant immediately sensed Bergman’s deep unhappiness and unease. Though she’d worked with Hitchcock before, on Spellbound, the part of Alicia Huberman called for her to be far more vulnerable and much less in control—emotions uncomfortably close to her real life at the time. Grant instinctively took her under his wing, protecting her from the rigors of a role that frayed every raw nerve.

The two grew close as they worked through their intimate scenes between takes, and often talked late into the night—sometimes about their director, who once called Grant “the only actor I ever loved” but was, at times, his usual autocratic self with Bergman, perhaps to mask his growing feelings for her.

“Ingrid took acting so seriously—she was a splendid, splendid performer but she wasn’t very relaxed in front of the camera,” Grant recalled years later. “She spoke English beautifully, of course, but she would occasionally have problems with some of its nuances.

“One morning, she had difficulty with her lines,” he went on. “She had to say her lines a certain way so I could imitate her readings. We worked on the scene for a couple of hours. Hitch never said anything. He just sat next to the camera, puffing on his cigar.”

Fearing he might be making her even more self-conscious, Grant stepped away from the set. “Later, when I was making my way back, I heard her say her lines perfectly,” he said. “At which point Hitch said ‘Cut!’ Followed by ‘Good morning, Ingrid.'”

After filming one of the most famous scenes—where the camera swoops down the spiral staircase to zero in on the key in Bergman’s hand—Grant did something he’d almost never felt compelled to do on a set before or since: he kept a souvenir. More on that later…

As the summer of ’46 wore on, the Notorious set became more relaxed. Bergman and Hitchcock had become such friends that he even allowed her to—gasp!—make suggestions about certain scenes. And she and Grant, it was clear, would remain close, regardless of where life or movies took them. A few months later, at the 1947 Academy Awards, Grant declared, “I think the Academy ought to set aside a special award for Bergman every year whether she makes a picture or not!”

When the movie wrapped in August 1946, Grant made the unlikely segue into The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer, while Bergman headed to New York to star in Maxwell Anderson’s Joan of Lorraine. Wandering along Broadway one day, she ducked into a theatre to see Roberto Rossellini’s Open City and was powerfully struck by its rawness and lack of artifice. After seeing a second film by the director, she wrote to him with an unusual offer:

“Dear Mr. Rossellini, I saw your films, Paisan and Open City, and enjoyed them very much. If you need a Swedish actress who speaks English very well, who has not forgotten her German, who is not yet very understandable in French, and who, in Italian, knows only ‘ti amo,’ I am ready to come and make a film with you.”

He accepted.

After shooting Under Capricorn, her final film for Hitchcock, as well as Joan of Arc, based on the Anderson play, Bergman headed to Italy. Not long after, in April 1949, news of the married mother’s affair with her Italian director became public. The following February, while in the midst of a divorce and ugly custody battle, she gave birth to their son, Robertino. She and Rossellini married in May 1950.

Bergman was excoriated by preachers, politicians and pundits; she was even denounced from the floor of the US Senate, as if she belonged in the same company as Hitler and Mussolini. American studios slammed their doors, many colleagues turned their backs, and disillusioned moviegoers took to their fainting couches. “People saw me as Joan of Arc and declared me a saint,” she recalled later. “I’m not. I’m just a woman, another human being.”

The list of those who didn’t condemn Bergman was considerably shorter—and at the head of it was Cary Grant. He stood by her and defended her, staying in close touch through all her years in Italy.

But after almost eight years and six films together, Rossellini and Bergman parted in 1956—and by then, Hollywood was ready to “forgive” the actress. She returned to the States to take the lead in Anastasia, and promptly picked up an Oscar nod. The night of the ceremony, she was in Paris starring in Tea and Sympathy. In the event she won, there was only one person she wanted to accept the award on her behalf.

And she won. And he did.

Not long after, Grant teamed with director Stanley Donen to produce Indiscreet, and both dearly hoped that Bergman would sign on. Donen arrived in Paris to make a personal pitch—but, having already learned of Grant’s involvement, though nothing else, she was one step ahead of the director. Before he could even settle into the sofa, she said, “I want to put you at ease—I’m going to do the picture.” Then she asked him what, exactly, the picture was.

She would later learn that Grant—who knew her years in Italy had not been lucrative—was making sure she got a percentage of the gross receipts in addition to her fee. Oh and he had authorized a fabulous wardrobe for her, enlisting the aid of a fellow named Christian Dior.

By the time London location shooting began in 1957, Bergman and Rossellini had legally separated. Touching down at Heathrow Airport for a pre-film press conference, Bergman braced herself for the media jackals. She needn’t have worried. Grant was right there waiting.

“I was taken into the transit lounge for the press conference, and there was Cary Grant sitting up on the table,” Bergman later recalled. “He shouted across the heads of the journalists ‘Ingrid, wait till you hear my problems!’”

But the Fleet Street hounds weren’t taking the bait; they continued to howl at Bergman about her impending divorce. “Come on fellas! You can’t ask a lady that!” Grant gallantly quipped. “Ask me the same question and I´ll give you an answer. So you´re not interested in my life? It’s twice as colorful as Ingrid’s!”

Once the rescue mission was complete, filming could commence. In Indiscreet, a romantic comedy based on Norman Krasna’s Kind Sir, Bergman plays Anna Kalman, a glamorous and accomplished actress who falls for Philip Adams (Grant), a world-renowned economist trapped in a loveless marriage with no hope of escape. At least that’s the tragic tale he’s woven for her. In reality, as we learn early on, it’s just an elaborate ruse to avoid serious involvement.

Their chemistry practically pours off the screen, whether they’re nuzzling in the drawing room or sharing the details of their day, split-screen, on the phone. She’s warm, he’s cool. She’s discreet, he’s direct. “Cary was always quick off the trigger,” director Stanley Donen remembered. “Bang—it was there. That was delightful. Ingrid just had a slower tempo. But it wasn’t a problem—they were magic together.”

The whole film feels like a dance of sorts, but there’s also an actual dance scene, which is beyond fabulous. Anna’s discovered the truth about Philip and is seriously pissed. (“How dare he make love to me and not be married!”) But, never one to ruffle an elegant evening, she lets him lead her to the floor anyway. Oh and watch for the moment when Grant bursts into a fabulous, loose-legged jig:

When shooting wrapped, Bergman found a small, neatly wrapped package in her dressing room. Tucked inside was the key to the wine cellar, from Notorious, which Grant had slipped into his pocket as a keepsake years earlier, when they first became friends. With it was a note urging Bergman to keep the key for good luck.

Their last public appearance together was in 1979, when Bergman, looking luminous in royal blue, hosted the American Film Institute’s tribute to Hitchcock:

In the glorious closing scene of Notorious, the desperately ill Alicia clings to Devlin and whispers, with all the strength that’s left in her, “Oh you love me, you love me…” And he assures her, “Long ago, all the time, since the beginning…” And so it was with Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman.

Here’s to Margaret Dumont—Who Always Got the Joke

“I’m not a stooge, I’m a straight lady—the best in Hollywood. There is an art to playing the straight role. You must build up your man but never top him, never steal the laughs.” — Margaret Dumont in 1937, discussing A Day at the Races, her fifth of seven films with the Marx Brothers.

Take that, Groucho.

For some reason known only to him and perhaps his therapist, the middle of the five Marx boys always insisted that Dumont never got the joke—even repeating the slight in his Honorary Oscar acceptance speech. It was cruel, it was self-serving, and it was clearly untrue.

For starters, she was from Brooklyn—where they grow trees, not saps. Born Daisy Juliette Baker in October 1882, Dumont was sent South as a child to be raised by her godfather, writer Joel Chandler Harris of Uncle Remus fame. But while still a teenager, she headed back to New York to take up a life in the theater, first as Daisy Dumont, then as Marguerite, and finally Margaret. As you might have guessed from her booming voice that somehow trilled at the same time, she also trained in opera, touring in America and Europe (as did W.C. Fields’ favorite foil, Kathleen Howard; more on her incredible life here).

Dumont made her stage debut in 1902, in The Beauty and the Beast in Philadelphia’s Chester Theater. She also moonlighted in vaudeville down the road in Atlantic City, quickly gaining notice as a “statuesque beauty” who could also carry off a quip with grace and ease. One reviewer presciently noted her “queenly dignity and hauteur.”

In 1910 she left behind a promising career to marry industrialist John Moller Jr., heir to a sugar fortune, sneaking in just one minor film role (fittingly, as an aristocrat in 1917’s A Tale of Two Cities) during their eight-year marriage. But when Moller died suddenly in 1918, Dumont, who never remarried, turned back to the stage for solace.

The young widow worked steadily on Broadway through the mid-1920s, when playwright George S. Kaufmann fell in love with her portrayal of a flighty matron in The Fourflusher. He tapped her for the role of Mrs. Potter, the perpetually put-upon dowager, in The Cocoanuts—thereby sealing a marriage made in comic heaven. (Dumont: “You must leave my room. We must have regard for conventions.” Groucho: “One guy isn’t enough. She’s gotta have a convention.”) She and the Marx Brothers reteamed on stage for Animal Crackers in 1928, and soon after, the whole troupe headed over the 59th Street Bridge to Astoria, Queens to shoot both plays as films for Paramount.

But most moviemakers were going West, and there was little doubt that when the boys headed to Hollywood, Dumont was going right along with them. Over the next 12 years and five films—Duck Soup, A Night at the Opera, A Day at the Races, At the Circus and The Big Store—she was the haughty, high-handed, wholly immovable object against which they threw every unstoppable force (including, in Duck Soup, tomatoes). She was the too, too solid center around which every plot, such as it was, revolved—her quicksilver features flickering from horror to amusement to affection to bewilderment and back again before you could say “Tuscaloosa.”

And it wasn’t only audiences who took notice. By the 1940s, just about every funnyman in town was lining up to work with Dumont, including W.C. Fields (Tales of Manhattan and Never Give a Sucker an Even Break—where Fields romanced Mrs. Hemogloben at her mountain retreat), Abbott and Costello (Little Giant), Laurel and Hardy (Dancing Masters), Danny Kaye (Up in Arms), Red Skelton (Bathing Beauty) and Jack Benny (The Horn Blows at Midnight).

Dumont continued to work steadily through the 1950s, mostly in television, including with Martin and Lewis on The Colgate Comedy Hour and with Bob Hope and Dinah Shore on their variety shows. Her final film role was as Shirley MacLaine’s mother in What a Way to Go! and her last TV performance was, appropriately, opposite Groucho in an update of the Captain Spaulding scene from Animal Crackers for The Hollywood Palace. On March 6, 1965, just eight days after the episode was taped, she succumbed to heart failure at age 82.

Dumont, who looks great, is in top form, as imposing as ever—breaking character only a few times to laugh, including when Groucho quips, “Don’t step on those few laughs I have.” And she sneaks in one other little bit of business: When Groucho leeringly jokes about his pictures of the native girls “not being developed yet,” she playfully pauses and then feigns an “Aha!” moment, as if she’s finally getting the joke for the first time. Talk about no good gag going unpunished…

In an interview with Dick Cavett several years later, Groucho dredged up the tired trope about Dumont not getting the jokes, and then recalled the 1965 TV session in especially ugly terms, claiming she behaved “as if she was still a big star,” sitting backstage clutching roses “that she probably bought herself.”

Now, I’m guessing that whenever a lady appeared on The Hollywood Palace, the producers left a bouquet in the dressing room. But even if Groucho thought she’d brought her own, why on earth would he be so nasty as to say so on national television? This is a woman who was as responsible as anyone on earth for the success of his films, whom even he sometimes called “the fifth Marx brother.” But maybe that’s precisely the reason he felt the need to take her down a peg or ten.

In deriding Dumont as dumb and haughty—even pathetic—Groucho was giving himself full marks as the brains behind their comic chemistry. After all, you can’t get credit for something you don’t know you’re doing. But in comedy, timing and rhythm are everything—and if you don’t get the gags, you’ll be hopeless on both counts. So why would the Marx Brothers use someone so clueless in seven films? And why would just about every other comedian in Hollywood snap her up as well?

Because she knew exactly what she was doing, that’s why. If her character had appeared to get the jokes—if they hit her smack in the face rather than gliding over her carefully coiffured head—they wouldn’t work at all; they’d just seem cruel. (How could we ever root for Groucho if he said something like, “I can see you right now in the kitchen, bending over a hot stove. But I can’t see the stove!” to a woman who knew what he meant?)

“The more one examines her early record, the less likely become all the later stories about her lack of humor or awareness of the Marx Brothers’ jokes,” writer Simon Louvish wryly noted in Monkey Business, his biography of the brothers. “It is not therefore Margaret Dumont who failed to see the joke, but the Marx Brothers, their interpreters and biographers, who have been unwitting victims of a desperate practical joke played upon us for three-quarters of a century by that greatest of dissimulating comediennes.”

I’ve often wondered why, when Groucho leveled his insulting charges, Dumont didn’t buttonhole a reporter or two to defend herself. The answer, I suspect, is that she was—not like the dowagers she played, but in a very real sense—a lady. And perhaps she thought the idea of her not getting the humor was a pretty funny gag. After all, this was a woman who always appreciated—and understood—a good joke. Even one at her own expense.

At the Capitolfest, Mickey Rooney Mixes It Up with Cowboys in MY PAL, THE KING

Have you ever wished you could watch a 1930s movie in the 1930s? I kinda had that chance last weekend at CapitolFest, a weekend of silent films and early talkies screened at the old Capitol Theatre in Rome, N.Y.

The 1788-seat movie palace looks much as it did when these films first flickered to life on its 20-by-40-foot screen, while the lively strains from the deco-style Möller organ welcomed well-dressed patrons to their seats for a Saturday-night date.

For most of the movies during CapitolFest weekend, I sat downstairs, cocooned under the massive domed ceiling. But for one film, I sneaked up to the balcony. It just felt right somehow. And while they’re doing a fabulous job renovating and restoring the entire place, a few old seats in the back of the theater were calling my name. And if anything was needed to make my trip back to the 1930s complete, this was it: there were metal braces to hold hats on the underside of the cushions.

I sank into one of the creaky seats, hoping I wouldn’t become so intimately familiar with the springs that I’d feel like I should light a cigarette afterward. Then I closed my eyes, imagining I had a straw hat tucked under the cushion and a cold bottle of Nehi Cola in my hand. And the curtains parted…

Onto the screen rode Tom Mix, co-starring with Mickey Rooney in Kurt Neumann’s My Pal the King (1932). Shot in just 12 days, this movies was way more fun that it had any right to be. I have to admit I’d never seen a Tom Mix movie, or any of the other old oaters. But boy, was he likeable. Already in his 50s by the time this was made, he was as sturdy, comfy and well broken in as an old rowboat. And just about as wooden. But his ropin’ and rasslin’ skills, and just plain aw-shucks-ness, more than made up for that. And Mickey, playing a boy king in one of his earliest full-feature roles, was just about the youngest and cutest I’ve ever seen him—12 going on four.

In the film, Mickey plays 10-year-old King Charles, the royal head of a mythical European country. Lonely, bored, and eager to be a real kid, he sneaks away to the town square (the same one used earlier in Frankenstein, minus the villagers in lederhosen), where he spies a fabulous traveling Wild West show headed by cowboy Tom Reed (Mix). Charles then invites him to perform at the palace, where he becomes a much-needed counterweight to the graspers and schemers surrounding the boy—including the treacherous Count DeMar (you knew there’d be an evil count, right?), played with moustache-twirling glee by James Kirkwood.

Fearing that the cowboy is becoming too darn good an influence on Charles—who’s relying less and less on his official advisors—the count and his band of evildoers kidnap the king and imprison him in the dark, damp catacombs of the count’s castle, where steadily rising waters threaten to engulf him. Mercifully, the waters only rise until they get to his shoulders, and then pretty much stay there for 10 minutes or so until Tom rides to his rescue. Formulaic? Maybe. But thrilling? Oh my, yes! I suddenly realized for the first time what my Dad felt like when he ran around the corner to the Stanley Theater in Brooklyn as a kid, with a quarter in one hand and his eyeglasses in the other.

“I try to make the pictures so that when a boy pays, say, 20 cents to see it, he will get 20 cents worth, not 10,” Mix once said. “If I drop, you see, it would be like putting my hand in his pocket and stealing a dime.” I can safely say that no money was stolen at the Capitol Theatre that day. It was a wonderful ride…

THE MAN I LOVE: Ida Lupino Rides to the Rescue of, Well, Everyone

In The Man I Love, Ida Lupino enters smoking.

She’s also got a cigarette.

If, after this, you wouldn’t want to stick around for the rest of the movie, just please don’t ever speak to me again.

It’s clear that for Petey Brown, the man she loves has come along… and come and gone. And like most of Lupino’s ladies, this one’s in deep.

Seeking some sort of sanctuary, Petey flees New York to spend Christmas with her family back home in California, where things seemed so much simpler. But they’re not so simple any more.

Her sister Sally (Andrea King) and brother Joey (Warren Douglas) are knee-deep in sleaze, working at a local dive owned by a shady hustler, Nicky Toresca (Robert Alda). Nicky has eyes for Sally, who’s got enough trouble tending to her shell-shocked, hospitalized husband (John Ridgely). Little sister Ginny (Martha Vickers) isn’t in trouble yet: she’s too busy babysitting for Gloria (Dolores Moran), the floozy next door, while the not-so-doting mother is out making time with Nicky. But Ginny’s starting to feel something more than pity for Gloria’s husband Johnny (Don McGuire).

Sorry you came home yet, Petey? Actually, no—she’s thinking she got there just in time. Petey, who was probably mothering this brood even when they still had a mother, is a rescuer in search of a mission. And boy, has she found one.

First order of business: pouring herself into the slinky gown the predatory Nicky had sent to Sally and sashaying down to his place to land a job as a singer, so she can keep an eye on the boss and distract him from her baby sister. Mission accomplished, with relative ease. What she wasn’t counting on was San Thomas (Bruce Bennett), the jazz pianist with a troubled past…

And just like that, Petey has another rescue on her hands—but this one’s not so eager to be saved. “I’d make you sing the blues, honey,” San warns her. “I’ll take that chance,” she murmurs back, and she means it, whatever the cost. San is broken, bruised and brooding from a bad marriage, and certain he has nothing left to give. Petey thinks otherwise, and when you see them together, in scenes so intimate you feel like you’re eavesdropping, you know she’s right.

And if you think of Bennett mainly as the helpless prospector in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre or the hapless husband in Mildred Pierce (where he somehow manages to look like the victim even though he’s the one cheating), take another glimpse. This is a man in pain, whose sensitive soul has brought him nothing but misery. His music was his refuge, until he met a woman as wounded as he is, who won’t let him hide in there alone any more. Watch him at the piano, playing the title song as Petey looks on tenderly, falling in love with him and the music and the idea of maybe even being happy again. I dare you not to fall right along with her.

This was director Raoul Walsh’s fourth film with Lupino, after Artists and Models, They Drive By Night and High Sierra (where yes, Bogart was a thief and a murderer, but the real crime was the way he treated Ida). The director and his favorite star were both alchemists who could strike the perfect balance of tough and tender. They had a great rhythm together, and he later mentored her when she took her place behind the camera. Lupino’s co-star Andrea King said they reminded her of father and daughter.

Like Walsh and Lupino, The Man I Love is impossible to pigeonhole. Is it a noir? A semi-musical? A crime drama? A dreaded “woman’s picture”? Variety labeled it a “brittle sex romance.” Which actually sounds kinda painful. Maybe Martin Scorsese, who calls the film one of his favorites, sums it up best: “The Man I Love is dark—it’s a film noir musical, and it’s what I was going for in New York, New York.”

But whatever you call it, with Walsh firmly at the helm, the film never founders. It just works. And Walsh was every bit as forceful about playtime: when he was happy with what he’d shot, he’d boom “Cut! Print!” followed quickly by “Now it’s time for the cooking sherry!”

But there wasn’t enough sherry in all of Spain to make The Man I Love a happy set. Shortly before production began in the summer of 1945, Lupino—already exhausted from her wartime duties touring hospitals and selling war bonds on three continents—strained a stomach muscle while moving a heavy trunk and was ordered to bed to recuperate. Just four days into the shoot, her injury flared up again. “Sorry, I am laid up,” she explained in a telegram to Walsh. “Wanted to come to work but doctors said absolutely no. The hypos are helping. The dogs are barking. The cooking sherry does not do any good and I just shot my aunt Kate. Will do my best to make it Saturday.”

Still fatigued and in pain, Lupino returned to work during a blistering July heatwave, and production ground on, punctuated by the star’s frequent, if unavoidable, latenesses and absences as her health failed to improve. During one scene, she fainted—with only Robert Alda’s quick reflexes coming between her and the concrete floor—and had to be snipped out of her skintight evening gown to be revived.

Adding to the tension on the set were the daily war bulletins, constant complaints about cost overruns from the front office, and endless memos from the Breen Office bleating about the film’s “low moral tone…of adultery and illicit sex,” which forced countless rewrites. When the production mercifully wrapped in mid-September, it was 19 days behind schedule and $100,000 over budget

Ida being Ida, she took the weight of the entire fiasco onto her own slender shoulders, throwing a huge party for the entire cast and crew of more than 200 and insisting on dancing with every man at least once. She promptly sprained her ankle, hobbling off the bedeviled set for the final time on crutches.

Three Cheers for Eva Marie Saint! (And Happy Birthday!)

Happy 91st Birthday, Eva Marie Saint!!

I’m trusting that tons of vintage photos of this luminous star are all over the intertubes today. But here are some I needed to share with you. Please forgive the blurriness—I was in the bleachers with my little Brownie camera!

On the opening night of the TCM Film Festival, the stars who’ll be featured over the next few days walk the red carpet into Grauman’s Chinese Theater for the premiere film. Many stop and chat with reporters and the TCM interviewer, and wave to the crowd in the bleachers set up for the occasion, stopping to chat if there’s time.

This is what Eva Marie Saint did in 2013.

She paused along the way to talk to everyone. Not just other stars, but fans, reporters, anyone who wanted a moment with her—prompting audible harumphs and frustrated sighs from the trained professionals trying to get her to move it along already. And she had a very animated girl-chat with the lovely Anne Jeffreys, about what I don’t know, but she looked about 16 at the time.

Then she got to the bleachers—and as she reminisced about her early years, she suddenly broke into a cheer from her old high school days. Then she laughed out loud—she may be the only woman in the world who can guffaw elegantly—and said, “I have no idea what made me do that!”

Later in the Festival, Saint spoke after a screening of A Place in the Sun, taking the stage while still sniffling. “It always gets to you, doesn’t it?” she asked the crowd, and, spotting me in the first row face-first in my hankie, pointed to me and said, “There’s a girl after my own heart!”

During her interview with Robert Osborne, she confided she’d planned to be a teacher, and then showed us how wonderful she would have been at it—pausing between memories of her amazing career to dish out advice directly to the audience. Recalling her days as a model in a cold-water flat in Manhattan, with few acting prospects, she told us to never give up and always hang onto our sense of humor. When Osborne asked her the secret for staying fit, she leaned away from her host and toward us, and, with the zeal of a preacher, threw her arms out wide and said, “Walk! Walk a lot, every day. It also helps you think.” You got the feeling she was genuinely worried about us not getting out there enough. And when the interview was over, she applauded the crowd, genuinely overwhelmed by the waves of love sweeping her way.

In short, she was an absolute doll. No one wanted the interview to end, and if we weren’t all so damn law-abiding, we would’ve locked her in the theater and not let her go home.

And so I couldn’t let this busy holiday weekend pass without sharing these memories and pix with you, and wishing this wonderful woman a happy and healthy 91st. And hoping she’s out there walking, a lot.

The George Sanders Touch: Even More Fabulous When He Sings

Reposting so we can all sing Happy Birthday to George Sanders — while he sings love songs to us!!

Need a little warmth to soothe you through those chilly nights? Wrap yourself in The George Sanders Touch….. Songs for the Lovely Lady.

He had me at the over-long ellipses…

And you needn’t be content just to gaze at the cover of this hard-to-find album, where a slightly sleepy George, who always wakes up in a dinner jacket, slyly hands you a… carnation. (Can’t you just hear him at the photo shoot? “A single red carnation? Really? For God’s sake I give roses to the lovely lady who delivers my laundry!”)

Every song is right here…

One number simply flows into the next—you don’t even have to get up to turn the album over! (You can also buy this in MP3 format from a number of sources, including Amazon UK, but then you don’t get the fabulous visual of George.)

“To the millions of motion picture fans around the world, George Sanders exemplifies nothing so much…

View original post 886 more words

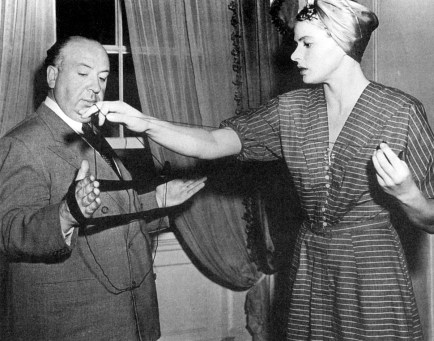

STAGE FRIGHT: Hitchcock Goes Home

As the 1950s rolled in, Alfred Hitchcock needed a change of pace. And a hit.

One out of two ain’t bad.

Stage Fright was certainly different: much lighter, for the most part, than most of his films and a return to his home turf, with an almost entirely British cast. But it was also a resounding flop—his fourth in a row, as filmgoers craved his more conventional thrillers and seemed impatient with movies that were harder to categorize, even if they were fabulous.

The previous decade had featured a string of classics that most directors would give their fortunes and families for: Rebecca, Suspicion, Saboteur, Lifeboat, Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, and the criminally underrated Mr. and Mrs. Smith and Foreign Correspondent. In their first collaboration, Hitchcock had mostly managed to keep Rebecca out of the clammy clutches of David O. Selznick. (According to director/film historian Peter Bogdanovich, Hitchcock recalled that as a climax, the producer wanted the smoke from the chimney to curl into the letter R. “Can you imagine?” he shuddered, even decades later.) But in their other two films together—Spellbound in 1945 and The Paradine Case in 1947—Selznick, who never met a thumpingly obvious flourish he didn’t like, had the gears more firmly in his grasp, with predictable results.

Hitchcock grew to loathe Selznick so much that he was still seething seven years after they parted. Does the uber-creepy wife-beheader in Rear Window remind you of anyone?

Smarting from his servitude with Selznick, Hitchcock cut loose with his own production company, Transatlantic Pictures, closing out the decade with the experimental Rope, which played with extended takes and fluid camera movements, and Under Capricorn, which used many of the same techniques, though less boldly. But neither made much headway with fans or critics, and together, the two financial failures sank his fledgling firm. Still, Hitchcock had reached a turning point: for the rest of his life, he would produce his own movies, under the auspices of larger studios.

Eager for a break from Hollywood, the director talked Warner Bros. into letting him make Stage Fright across the Atlantic. Shrewdly, he took along one of the studio’s biggest new stars, Jane Wyman—fresh off her Oscar win for Johnny Belinda—in the hope of boosting the box office.

Wyman plays Eve Gill, an aspiring actress at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (where Hitchcock’s daughter Patricia, who made her film debut as Eve’s friend “Chubby” Bannister, was studying at the time). Eve’s in love with Jonathan Cooper (Richard Todd), a young actor who’s having a secret affair with Charlotte Inwood (Marlene Dietrich), a flamboyant stage star. As the film opens, Jonathan breathlessly bursts in on Eve’s rehearsal and begs for help; we learn, via his flashback, that Charlotte came to see him after killing her husband and asked him to hide her bloodstained dress, and that when he went back to fetch her a change of clothes, he was spotted by Charlotte’s dresser, Nellie (Kay Walsh). And now he’s on the run from the police.

Eve spirits him off to the coastal cottage of her father, the Commodore (Alastair Sim), who notices that the blood seems to have been deliberately smeared on the dress. He warns Jonathan that Charlotte may be trying to frame him. Angry at the accusation against his lover, Jonathan throws the crucial evidence into the fireplace. And Eve is knocked a bit backward by his intensity.

With Jonathan parked safely if crankily with her father, Eve heads back to London, still determined to clear the man she perhaps loved a bit more an hour ago than she does now. When she stumbles across a detective (Michael Wilding, as “Ordinary” Smith) in a local pub, she feigns a fainting spell to get his attention—but this actress is just getting started. She tells Smith she’s a reporter working on the case, and later finagles her way into the role of Charlotte’s dresser, after paying Nellie off to disappear for a while…

The romantic sparks between the wide-eyed Eve and the shyly wry detective are clear from the moment he waves a brandy under her nose. During one scene in a taxicab, they stammer and stare and swoon until you’re practically screaming at the screen, “Oh for God’s sake, just kiss!” So now, Eve has to lie to the man she’s falling in love with to save the one she’s pretty much gotten over.

At one point, when Eve’s volunteering at a local fair, she’s shuttling among Smith, Charlotte and her schoolmates, playing three different roles. Meanwhile, her father, who’s now neck-deep in his daughter’s quest to help Jonathan (who, as far as he knows, she’s still in love with), is cheating some skinny little schnook at the shooting gallery, in order to win a doll whose dress he can smear with blood; he’s hoping to unnerve Charlotte—who’s performing at the fair—into confessing. The whole thing is hilariously nerve-wracking—and as if that weren’t enough, Joyce Grenfell is on hand to run the shooting gallery, urging everyone within her (very wide) earshot to try their luck with the “lovely ducks!”

Eventually, of course, Smith discovers Eve’s true identity and her motives, but sets aside his battered ego long enough to help her trap Charlotte. Still posing as the diva’s dresser, Eve tells her she has the bloodstained dress, suggesting she’d part with it for a price. Charlotte confesses that she did plan the murder but that Jonathan carried it out, and offers Eve £10,000 to keep her mouth shut. All of this is being picked up by hidden police micophones in the theater, and soon Charlotte is arrested, but Jonathan, who’s long since bolted from the Commodore’s cottage, slips the police net. Eve is certain Charlotte is lying about Jonathan’s involvement, and sets out to save him once again…

Caution: Spoilers Ahead…

This is just about the only Hitchcock film you’d need to do a Spoiler Alert for, since you usually know who the bad guys are right from the jump. But here goes. Remember Jonathan’s desperate recounting of how Charlotte showed up in the bloodstained dress, and all the flashbacks that followed? Yeah. Those were all humongous lies. Which Eve finds out the hard way—that awkward moment when the cute guy you had a huge crush on turns out to be a raving homicidal maniac…

Eve catches up with Jonathan in the trenches of the theater, and once they’re hidden away there, he tells her that Charlotte goaded him into killing her husband, and he’s the one who smeared the blood on her dress. He also confides his cunning plan to get away with it: kill Eve for no reason, to shore up an insanity defense. Suddenly things get much more Hitchcockian: victim and killer are thrown into sharp, shadowy relief, and it almost becomes a different film—in keeping with the sense that everything that has gone on before was mere artifice and now we, like Eve, are face to face with the dark and dangerous reality.

After several excruciating minutes, Smith and the police arrive and flush out the killer, who, attempting to flee, is caught and crushed under the stage’s (ironically named) safety curtain.

Critics and audiences came at Hitchcock with everything but pitchforks for the “lying flashbacks” from an unreliable narrator; the director countered that this was simply one character’s version of events and needn’t have been taken as gospel. But he later called it one of the biggest missteps of his long career.

I like his first take better. Over the years, moviegoers had grown to care deeply for Hitchcock’s wrongfully accused victims, and I understand how they might have felt betrayed. But it’s not a director’s job to spoon-feed people the same formula in film after film. I loved the surprise—and that, in a movie rife with deception, we were as fooled as Eve was. It put us right there with her in that dark corner, deepening our sympathy and adding another layer of emotion to a finale that’s as creepy and suspenseful as almost anything Hitchcock ever put on the screen.

…End of Spoilers

Stage Fright also has just about as much sheer chemistry as any of Hitchcock’s films. Wyman and the always-brilliant Sim are in perfect rhythm as father and daughter—quirky kindred spirits caught in the middle of a murder mystery. (Have you ever watched an Alastair Sim movie and tried to picture anyone else in his part?)

And Dietrich and Wyman play beautifully off each other as the glam goddess and the modest maid she takes under her wing, somewhat mirroring their relationship offscreen, which got off to a shaky start but ended with Dietrich insisting on retakes when she felt Wyman wasn’t lit properly.

Draped in Dior from start to finish, Dietrich is beyond fabulous, even when she’s being fitted for her widow’s weeds. “This is very nice, if you can call mourning nice,” she confides to her maid, “but isn’t there some way we could let it plunge a little in front?” (Dietrich’s own bracelet sets off every gown; the modest little bangle, made for her out of some stray diamonds and rubies she had lying around, sold for almost a million dollars at Sotheby’s in 1992.)

And finally, how many Hitchcock movies feature Dietrich purring through a Cole Porter song…

…which I’m pretty sure was the inspiration for this:

All in all, Stage Fright is Hitchcock’s most fearfully underrated film.

Recent Comments