Four Extraordinary Heroes, One Regiment: Basil Rathbone, Ronald Colman, Claude Rains and Herbert Marshall in World War I

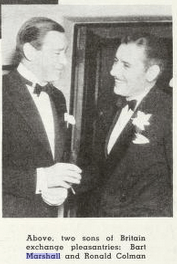

Basil Rathbone conceived an almost certain suicide mission—and carried it off disguised as a tree. Herbert Marshall, who lost a leg to a sniper’s bullet, downplayed his sacrifice, saying his most salient memories of the trenches were numbness and boredom. Claude Rains lost almost half his sight to a poison gas attack. And Ronald Colman barely dragged himself back to his barracks after being strafed by shrapnel in one of the earliest, bloodiest battles of the war.

World War I claimed over 17 million lives—or roughly one of every hundred human beings alive on earth when it began in 1914. By dint of their age at the time, many of our most beloved early film actors were among those who fought. This is the story of four who served valiantly—all in separate battalions of the same regiment.

The storied London Scottish Regiment, which saw some of the most savage fighting in France and Belgium, was headquartered on Horseferry Road in Westminster, in the heart of London, with a drill hall around the corner from Buckingham Palace—both within walking distance of the West End theatres. So it was a natural destination for young actors willing to leave the safety of the boards behind, putting their promising careers on hold and their lives on the line to volunteer for one of the ghastliest conflicts in all of history.

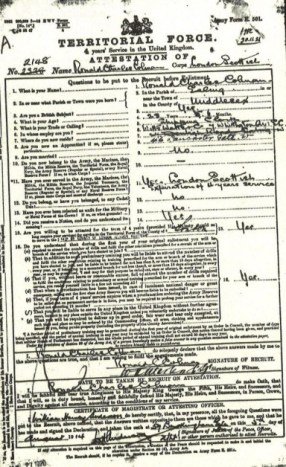

Ronald Colman was working as a shipping clerk and starring in amateur productions with the Bancroft Theatrical Society when the war broke out in July 1914—and he promptly enlisted the following month. Among the first British soldiers sent to the Western Front, where some of the worst fighting was already raging, Colman made it through the Battle of Ypres before his luck ran out. On Halloween night, he was thrown into the air by an exploding mortar shell in the brutal Battle of Messines in Belgium’s Flanders field, which killed or wounded almost 300 of his comrades.

“Amid the din of his army’s band, the shellfire, whizbangs, machine-gun bullets, the shouting of Germans and British alike, came an explosion unnoticed by all except Private Colman. Shrapnel ripped through his knee and ankle, throwing him face-first into the beetroot field. Finding himself unable to put any weight upon the mangled leg, he started to crawl back, dragging the broken bones, stumbling over his kilt, and trying not to pass out. During this maneuver, it suddenly occurred to him that should the next bullet or shell be lethal, he would be found dead with his back to the enemy, and at the rate the battle was going, this was more than a strong possibility. He had every intention of maintaining the dignity both of himself and of his country, whether or not he made it to safety. Without further hesitation, he turned onto his back, and pulling with his elbows, then pushing with his good leg, he retreated from the field of battle while facing the German lines.” — daughter Juliet Benita Colman, in Ronald Colman: A Very Private Person.

Colman was discharged as no longer physically fit for war service in May 1915, and later awarded the Silver War Badge as well as the Victory Medal and the British War Medal. His injuries left him with a permanent limp, which he disguised as a unique, even jaunty stride throughout his career. Other wounds were less visible and doubtless more common. Years later, Colman recalled:

“The war suddenly swooped down on us like a martial bird and bore us off. There was no time for goodbyes, either to family or sweethearts, movies and fiction to the contrary. We embarked from Folkstone. I remember sitting in that train with my battalion on a siding, waiting to go. I could see from my car window the familiar streets I had walked so many times, houses of people I knew. I felt as a dead man might feel, revisiting, himself unseen, old haunts he had known well but which knew him no longer. I knew that I would come back but not as I was then. Because I didn’t come back. I won’t go into the war and all that it did to all of us. We went out. Strangers came back. It was the war that made an actor out of me. When I came back that was all I was good for: acting. I wasn’t my own man anymore.”

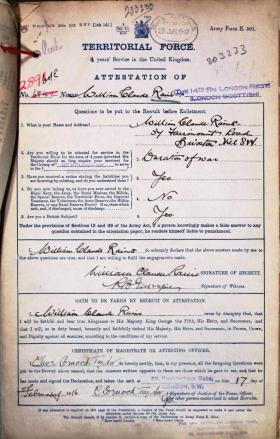

Claude Rains was already a successful working actor on both sides of the Atlantic when he enlisted in February 1916. “I was not heroic,” he said years later. “I just knew I’d be ashamed of myself if I did not. I didn’t want to be hurt, or hurt anyone else.”

In November, as they fought their way along the Vimy Ridge in northern France, Rains’ unit was bombarded with heavy artillery and poison gas. The noxious chemicals paralyzed his vocal cords and destroyed most of the vision in his right eye. His voice gradually returned, but with a huskier quality that would become his trademark.

Still fit for service though not for battle, Rains was granted an officer’s commission at a territorial unit based in the London borough of Croydon, where his commanding officer, Thomas Peak, described him as a “very intelligent scholar.” He served there as an adjutant until after the war in February 1919, leaving the army as a captain.

Despite his grievous injury, Rains seriously considered making the military his career, and was reportedly on his way to re-enlist when he ran into an old theatrical mate, who offered him a job with the Everyman Theatre company in London. The troupe specialized in the works of G. B. Shaw—including Caesar and Cleopatra, in which he’d later co-star with Vivien Leigh on film.

Herbert Marshall was three years into his acting career when he enlisted in June 1916—and was on his way to the Western Front in a matter of months. Like many who survived the war, he downplayed its more hellish aspects. “I knew terrific boredom,” he said years later. “There was no drama lying in the trenches 10 months. I must have felt fear, but I don’t remember it. I was too numb to recall any enterprise on my part.”

In April 1917, during the second Battle of Arras, Marshall was shot in the right knee by a sniper and taken to a medical unit at Abbéville before being transported home to England, where he remained in the hospital for more than a year. After a series of complex operations to try to save his leg, doctors were finally forced to amputate near the hip.

Marshall was initially racked by bitterness and despair, all but certain that a return to the theatre, or even to a normal life, was all but impossible. He credited a beloved uncle, Leopold “Bogey” Godfrey-Turner—who had lost his oldest son in the war—with saving him from self-pity: “He had a lavish joy in life, an embattled mind, keen wit, sensitive appreciations and a gallant soul, and proved to me that a man may face utter desolation without whimpering. By his fine courage and by his gorgeous humor, which not even grief could crucify, he showed me how a man may know irreparable loss and still inherit the earth. When I learned to walk again, I returned to London, healed in spirit if not in body, and all because of Uncle Bogey.”

While Marshall was undergoing rehabilitation in St. Thomas Hospital, King George V made the rounds of the wards, visiting wounded soldiers. Challenged to pick which of his legs was the prosthesis, the king picked the wrong one.

Other than his distinctive square-shouldered, deliberate gait and his need to be doubled in certain scenes, Marshall’s injury had virtually no impact on his performances. But he suffered from “phantom pain” and from the discomfort of the prosthesis for the rest of his life. He had holes cut in the pockets of his trousers so he could loosen the strap when it became especially excruciating. In later years, as the pain grew stronger, he developed a more pronounced limp.

For his valor and sacrifice, Marshall was awarded the Silver War Badge, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

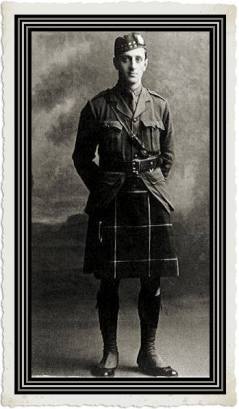

Basil Rathbone seemed destined for the crucial role he played late in the war: that of a spy. In 1895, during the Second Boer War, his family had been forced to return to England from South Africa after the Boers accused his father of carrying out espionage for the British government.

Like so many others, he was horrified by the senseless nightmare unfolding across Europe. “I felt physically sick to my stomach, as I saw or heard or read of the avalanche of brave young men rushing to join,” he later wrote in his memoir, In and Out of Character. “Was I ‘pigeon-livered’ that I felt no such call to duty—that I was pondering how long I could delay joining up? The very idea of soldiering appalled me. Most probably somewhere in Germany there was a young man, with much the same ideas as I had, and one of us was quite possibly destined to shoot and kill the other. The whole thing was monstrous, utterly and unbelievably monstrous—irrational, pitiable, ugly, and sordid.”

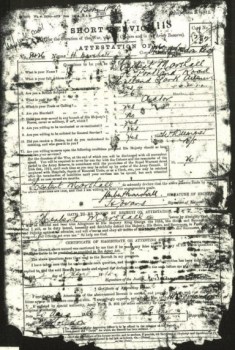

Still, in March 1916, Rathbone abandoned a promising career in the theatre and enlisted—prompted in part by the fact that his younger brother John (above center with Basil and sister Bea, and above right), with whom he was extremely close, had already been fighting for a year. After completing officers training camp, he was awarded a commission as a second lieutenant. At first, his battalion was held back in England, sparing him at least briefly from the horrors of the Western Front.

The following February, he contracted the measles, and after a brief stay in a military hospital was sent home to London—where John was recovering after being shot in the chest and nearly killed at the Battle of Somme. When the measles subsided, Rathbone rejoined his battalion, which was by then neck-deep in the muddy trenches of Bois-Grenier. But despite his own travails, his thoughts continually turned to his brother. That autumn, he wrote to his father:

I had a letter from Johnny the other day, saying he hopes to be back here soon. He surely can’t be well enough yet? I had thought he would be out of it for at least the rest of the year. He has scared us enough for the present and I shan’t enjoy worrying about him again.

But John did return to France, in the spring of 1918. “His regiment, The Dorsets, was stationed close by and he had leave to come over and spend the night with me,” Rathbone wrote in his memoir. “John and I spent a glorious day together. He had an infectious sense of humor and a personality that made friends for him wherever he went. In our mess on that night he made himself as well-liked as in his own regiment. We retired late, full of good food and Scotch whiskey. We shared my bed and were soon sound asleep. It was still dark when I awakened from a nightmare. I had just seen John killed. I lit the candle beside my bed and held it to my brother’s face—for some moments I could not persuade myself that he was not indeed dead. At last I heard his regular gentle breathing. I kissed him and blew out the candle and lay back on my pillow again. But further sleep was impossible. A tremulous premonition haunted me—a premonition which even the dawn failed to dispel.”

His next premonition was chillingly accurate: “At one o’clock on June 4, 1918, I was sitting in my dugout in the front line. Suddenly I thought of John, and for some inexplicable reason I wanted to cry, and did. In due course I received the news of his death in action at exactly one o’clock on June the fourth.” Their mother had died just months earlier.

A month later, in a letter to his father, Rathbone wrote:

We came up from the reserves a while ago, and just before we left I had your letter and also the parcel from uncle H. Please thank uncle and all the family especially the girls for their dear little poems. The whisky has already proved helpful. I shared the cake with my men and it was consumed in three minutes and pronounced to be pretty fair, which is high praise.

I’m sorry for the awful handwriting but it’s very cold and I’m shivering terribly and there’s only an inch of candle left in the dugout to write by and it flickers. It’s 3:50 so bitterly cold I’m wearing my great coat though it’s July, but it’s been a quiet night, and when I was out I caught a nice moon, very bright between little bits of cloud. I think it will be a very bright and sweet and warm day again like yesterday. Cloudless and a little breeze. Just the day for cricket.

Today will be quite a busy one and so I want to send this before it gets going.

I have all of Johnny’s letters parcelled up together and I will either bring them home on my next leave or arrange for someone to deliver them in person. I would send them as you asked but I would be afraid of them being lost. The communication trenches can take a beating and nothing can be relied on. If I can’t bring them myself for any reason there is a good sort here, another Lieutenant in our company who is under oath to deliver them, and who I have never known to shirk or break his word. So, you will get them, come what may.

I’m sorry not to have written much the past weeks. It was unfair and you are very kind not to be angry. You ask how I have been since we heard, well, if I am honest with you, and I may as well be, I have been seething. I was so certain it would be me first of either of us. I’m even sure it was supposed to be me and he somehow contrived in his wretched Johnny-fashion to get in my way just as he always would when he was small. I want to tell him to mind his place. I think of his ridiculous belief that everything would always be well, his ever-hopeful smile, and I want to cuff him for a little fool. He had no business to let it happen and it maddens me that I shall never be able to tell him so, or change it or bring him back. I can’t think of him without being consumed with anger at him for being dead and beyond anything I can do to him.

It’s clear, as he writes of having “someone else” deliver his brother’s letters if he cannot and how his father will get them “come what may,” that he all but expected to die. Decades later, in a letter to a friend, he said that during these months, he was “dragging this living corpse of myself around, giving it things to do, because here it was, alive. I followed paths that were there to be followed, I did what others said to do. I didn’t care.”

Rathbone had been leading nighttime patrols into No Man’s Land, the treacherous and often lethal stretch of ground between the enemy camps, which was strewn with the bodies of soldiers from both sides. Shortly after learning John had been killed, he went to his commanding officer with an even bolder plan.

“I said that I thought we’d get a great deal more information from the enemy if we didn’t fool around in the dark so much… and I asked him whether I could go out in daylight,” he recalled in a 1957 interview. “I think he thought we were a little crazy…”

So just imagine his reaction when the eager lieutenant said they should go out on these raids disguised as trees. “I suggested we use camouflage, a device I had first learned under very different, though not always more peaceful circumstances, and which would compensate us somewhat for the loss of anonymity afforded by darkness,” Rathbone relayed in his memoir. And almost at once, the daring mission was underway: “On our heads we wore wreaths of freshly plucked foliage; our faces and hands were blackened with burnt cork. About 5:00 a.m. we crawled through our wire…”

Rathbone and three comrades crept almost imperceptibly slowly across the 200 yards of No Man’s Land, finally reaching the enemy’s front line: “Suddenly there were footsteps and a German soldier came into view behind the next traverse. He stopped suddenly, struck dumb, no doubt, by our strange appearance. Capturing him was out of the question; we were too far away from home. But before he could pull himself together and spread the alarm, I shot him twice with my revolver… Tanner tore the identification tags off his uniform and I rifled his pockets, stuffing a diary and some papers into my camouflage suit… We scaled the parapet, forced our way through the barbed wire… and had hardly reached it when two machine guns opened a cross fire on us.”

Rathbone and his men fled off in different directions, diving from one crater to the next until all four finally made it back to base.

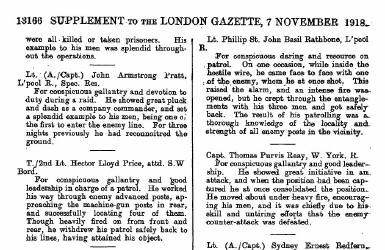

His commanding officer sent reports to the war office praising the daring daylight raid, which yielded crucial information on upcoming troop movements, and Rathbone was awarded the Military Cross “for conspicuous daring and resource on patrol.” That he survived such a firefight was nothing short of miraculous—but it wasn’t until he was safe in his dugout that the full toll of the war hit him the hardest. “In one of the shell holes on the way back I had stepped into a decomposing body,” he recalled. “Right there I removed the boot, and someone stuck a bayonet into it and heaved it back into No Man’s Land… With one shoe off and one shoe on, the reality and horror of war came rushing in on me.”

TINTYPE TUESDAY: Keaton, Valentino and Nazimova, Ready for Their Arthur Rice Close-Ups

Welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY! When you think of classic-film portraits, who pops to mind? George Hurrell, Clarence Bull, Ruth Harriett Louise?

What about Arthur Rice?

When it comes to recognition, Rice seems to have been left largely on the cutting-room floor. But his work was nothing short of stunning, capturing in still life what the best silent-film cinematographers captured in motion—the moody play of light and shadow, the dramatic intensity, the dreamlike spirit.

During the late 1910s and early 1920s, Rice shot film stills and portraits for Metro Pictures, the forerunner of MGM, which distributed many films of stars such as Buster Keaton, Rudolph Valentino and Alla Nazimova. Here’s a sampling of his gorgeous work.

Portraits of Keaton:

Portraits of Nazimova:

Valentino and Alice Terry in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse:

Valentino and Nazimova in Camille:

Nazimova as Salome:

Nazimova as Camille:

Are you sighing yet? Thank Arthur Rice, a sensitive, undersung artist who gave us an enduring glimpse into an ethereal, long-ago dream.

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and usually a bit of backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

Of Dads, Dreams and the Damn World Series

Watching the final game of the World Series, as our home team was ground to bits by a baseball machine known as the Royals, one classic film kept running through my mind. I’m guessing you know which one.

The Royals were the best team in baseball this year. If you’d plugged all the variables into some fancy algorithm to determine who’d win the Series, the outcome would have been exactly as it was. But baseball’s not supposed to be that way.There’s a reason Damn Yankees wasn’t made as Damn Celtics or Damn Montreal Canadiéns. Because baseball’s the only sport where the old cliché about “any team winning on any given day” is actually true. Where heart can take you places algorithms can’t even dream of.

Before the season started, the Mets were 50-1 long shots to win the Series, and faced similarly long odds of even making it there. In the first round of the playoffs, they weren’t expected to beat the Dodgers even before their shortstop’s leg was broken on a sleazy, super-illegal slide by a guy who still hasn’t touched the base he claims he was aiming for. Then they were underdogs against Chicago and up against the Back to the Future curse to boot—in the film, the Cubs win the 2015 World Series—but somehow dug so deep that they swept them.

They played with all their hearts, and way over their heads. Then they dragged their batterered, bruised bodies into the Series—straight into the headlights of an unstoppable freight train, all steel and speed. The Royals were not only gifted, but ruthless, capitalizing on every mistake and lunging at every opportunity, always coiled for the kill. And good for them.

But you know what? I really hate people like that.

The Mets bobbled grounders. They rushed throws to the plate. They took wild, semi-desperate swings. And in the final game, the manager let his heart rule his head and left his ace in too long. His explanation? “It was my fault… I love my players.”

That’s a fault?

The Mets were anxious, overemotional, illogical, imperfect. I like people like that. I am people like that.

I could hear my Dad saying, “Catch it before you throw it!” and “Jeez, look the pitcher over!” He taught me baseball, and introduced me to classic films. Those were the two things we watched most often together, and oldmoviesbaseballDad will always hold one unbroken space in my heart. He had only 46 years on this earth, and I was only 16 when I lost him. But I have never, ever watched a baseball game or old movie without feeling he was there beside me.

And I know somewhere up there he was shaking his head last night over the Mets, but loving them anyway. This morning, I took some of the buttons he gave me out of a drawer, and remembered the too-few seasons we watched games together. I couldn’t remember any of the specifics—the plays, the scores, who won, who lost. All that came flooding back were the feelings.

Watching the last inning of the World Series, I was thinking of Damn Yankees, and wishing that, as in the film, heart would prevail over might. But either way, I knew which side I was on.

You gotta have heart. Because even when it’s fumbling, flailing and falling apart, it’s still better than anything else.

STREAMING SATURDAY!! Gather Round for Tales of Terror from Basil Rathbone, James Mason and Christopher Lee!

Happy Halloween, my fabulous family of friends! Welcome to a special edition of Streaming Saturdays!

Gather round as Basil Rathbone, James Mason and Christopher Lee, three of the most compelling taletellers in all of classic film, share some of their favorite poems and stories by Edgar Allan Poe. Mason reads The Telltale Heart and Silence; Lee reads The Fall of the House of Usher and The Raven, and Rathbone reads The Cask of Amontillado. As an added bonus, The Telltale Heart is set to a cartoon from the amazing animators at UPA!

So listen, my children, and you shall hear… delicious tales of dread and fear!

The Telltale Heart:

Silence:

The Fall of the House of Usher:

The Raven:

The Cask of Amontillado:

HAPPY HALLOWEEN!

STREAMING SATURDAYS is a regular feature on Sister Celluloid, bringing you a free fun film every week! You can catch up on movies you may have missed by clicking here! And why not bookmark the page to make sure you never miss another?

Please Join Us for the Backstage Blogathon!

I’m thrilled to be co-hosting another blogathon with the fabulous Fritzi at Movies Silently! And this one premieres in—gasp!—2016. Which is much closer than you think.

On that cheery note, please join us January 15-18 for the Backstage Blogathon!

What’s it about? Well, the entertainment industry has always loved looking in the mirror, and we’re going to be taking a peek at what they put on the screen as a result—from love letters to scathing indictments and everything in between.

This isn’t limited to movies about movies: You can pick films that go behind the scenes of any performing art: ballet, theatre, puppetry, opera, the circus… use your imagination!

The film must feature performing arts as a significant part of the plot. So it’s not enough for a character to simply be, say, an actress; the profession must play an important part in the story. John Cassavetes, for instance, plays a struggling actor in Rosemary’s Baby, but the movie’s about communing with Satan, who in this case is not Louis B. Mayer.

To join up, all you have to do is tell either Fritzi or me your film choice. All movies must be from 1970 or before and, considering how often the arts have gazed at themselves on film, no duplicates are allowed—we are confident there’s something for everyone! Animated films are welcome, as are foreign movies. But no documentaries, please.

Here are some suggestions: Make Me a Star, Film Film Film, Ella Cinders, Our Gang Follies of 1936, All About Eve, The Oscar, Forever Female, Valley of the Dolls, A Star Is Born (Janet Gaynor or Judy Garland but not, heaven forbid, Barbra Streisand), The Big Knife, Black Widow, Lili, Pinocchio, The Hard Way, The Mind Reader, Nightmare Alley, Trapeze, At the Circus, A Night at the Opera, Freaks, He Who Gets Slapped, Laugh Clown Laugh, The Unknown, Berserk, Sunset Boulevard, The Next Voice You Hear, Shine on Harvest Moon, It’s a Great Feeling, Summer Stock, Love Me or Leave Me, Bombshell, Dancing Lady, Svengali, Sullivan’s Travels, and biopics of performers.

And to answer a couple of other questions in advance:

I have great behind-the-scenes stories of a famous film. Can I write about those?

No. We’re covering how movies portray the entertainment industry. Of course, if you have some juicy anecdotes about the backstage film you are covering, feel free to include them.

Can I write about authors and painters?

While we all love us some Kirk Douglas as Van Gogh or Norma Shearer as Elizabeth Barrett Browning, they’re for another blogathon another day. This event centers around the performing arts. Other forms of art can be featured but the movie must focus on acting, singing, dancing etc. as the main theme.

Once you sign up, please take a banner from this post and place it in your blog’s sidebar. We’re so happy to have you aboard! (We also understand that life happens, so if you find you can’t make the event after all, please let us know as soon as you can so we can free up that film for another blogger to claim. Thanks!) Grab a movie and let’s go backstage!

The Roster So Far:

Movies Silently Kean and No Way to Treat a Lady

Sister Celluloid Souls for Sale

Criterion Blues The Red Shoes

Speakeasy The Lost Squadron

A Shroud of Thoughts 42nd Street

B Noir Detour A Double Life

Now Voyaging Show People

Silver Screenings Footlight Parade

The Motion Pictures Annabel Takes a Tour

The Last Drive In The Legend of Lyla Claire

Citizen Screen Daffy Duck in Hollywood

Movie Movie Blog Blog You Ought to Be in Pictures

Caftan Woman Charlie Chan at the Opera

Make Mine Criterion Hellzapoppin’

Carole & Co. Twentieth Century

Defiant Success Yankee Doodle Dandy

Love Letters to Old Hollywood There’s No Business Like Show Business

Stardust Singin’ in the Rain

Nitrateglow The Unknown

Mildred’s Fatburgers Kiss Me Kate

Wolffian Classic Movie Digest The Bad and the Beautiful

Cinematic Scribblings 8 1/2

Cinema Cities The Barkleys of Broadway

Immortal Ephemera What Price Hollywood?

Moon in Gemini Unfaithfully Yours

Smitten Kitten Vintage Easter Parade

Cinephiliaque Contempt

Tam May, Author Stage Door

The Movie Rat Our Gang Follies of 1936

Critica Retro The Phantom of the Opera (1925 and 1943)

The Joy and Agony of Movies All About Eve

David Bruce Appreciation Society Alice in Movieland

Cinema Shame A Night at the Opera

Second Sight Cinema The Gang’s All Here

Girls Do Film Contempt

Cinema Gadfly Variety Lights

Wonderful World of Cinema Lady Be Good

Scribblings Upstream

LA Explorer Babes in Arms and Babes on Broadway

Welcome to My Magick Theater Abbott and Costello in Hollywood

Phyllis Loves Classic Movies What a Great Feeling and Funny Girl

Old Hollywood Films Summer Stock

Pop Culture Pundit Sunset Boulevard

Crimson Kimono They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

Tossing It Out Idiot’s Delight

Wrote by Rote Give My Regards to Broadway

The Love Pirate The Producers (1967)

BB Creations The Band Wagon

Laini Giles Ziegfeld Girl

TINTYPE TUESDAY: Classic Film Stars at Their Fabulous Costume Parties!

Welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY! Happy Halloween, my fabulous family of classic film friends… and what’s Halloween without a costume party or ten?

If this were the 1930s (and let’s face it, in our hearts, it is), we’d all be heading off to a dress-up ball at William Randolph Hearst’s place in San Simeon, where Marion Davies would be holding court, or Marion’s seaside villa in Santa Monica, or Basil and Oudia Rathbone’s ivy-covered hideaway in Los Feliz. These spots were pretty much Costume Party Central in Old Hollywood—unless the crowd was especially large, in which case the Rathbones took over a whole restaurant.

And it didn’t even have to be Halloween. After a long day of donning costumes, some of these folks loved nothing more than to slip into new ones at night. So let’s join them, shall we?

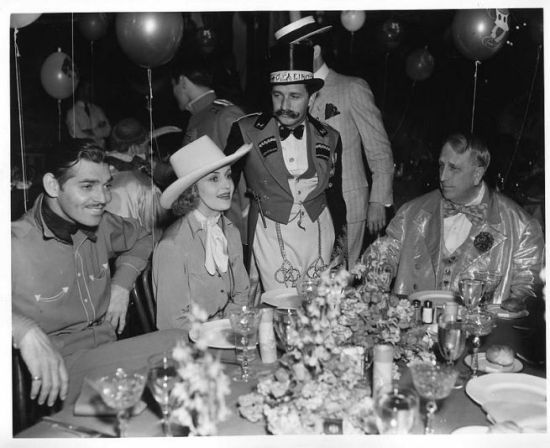

First stop: a circus-themed soirée in Santa Monica with Clark Gable, Carole Lombard and Mervyn LeRoy. And what big-top bash would be complete without a full-size carousel from Warner Brothers? Marion gave it a go before dining with Claudette Colbert.

For her Alpine bash, I’m not sure if Marion brought in any actual Alps. But she did get Gloria Swanson, Jean Harlow and Harpo Marx into the spirit of things. Still, no power on earth could force Constance Bennett into a dirndl.

Clark Gable got in touch with his inner Boy Scout at the kid-themed party up San Simeon way! And he brought most of MGM with him, including the Talmadge sisters, Joan Crawford and Doug Fairbanks Jr., and Norma Shearer and Irving Thalberg.

Norma got to keep her head as Marie Antoinette at a costume party for W.R.’s birthday, where the guest of honor danced with Jean Arthur.

This party was more of an “anything goes” affair, and Marion played the clown, something she didn’t get to do often enough on screen! And as you might expect, Norma and Irving were a bit lower-key than Ouida and Basil…

…but Rudolph Valentino and Pola Negri outdid them all.

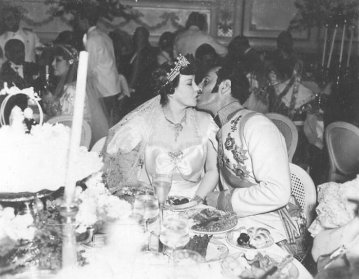

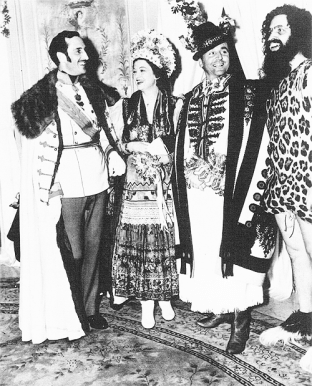

Speaking of Basil and Oudia, the duo were dubbed “Hollywood’s most successful party-givers” by Life magazine. And in 1937, for their 11th anniversary, they invited 250 of Hollywood’s finest to celebrate with them at the Victor Hugo Restaurant in Beverly Hills (which later became designer Adrian’s costume studio). Greeting their guests as Emperor Franz Josef and Empress Elizabeth of Austria, the couple issued just one small edict: that their guests arrive dressed as famous couples.

Gene Raymond and Jeanette MacDonald showed up as Romeo and Juliet, while Edward G. Robinson and his wife Gladys came as Napoleon and Josephine.

Here’s Basil greeting Cedric Gibbons, Dolores del Rio and Marlene Dietrich…

…and Myrna Loy and husband Arthur Hornblow. And yes, that’s Frederic March in a leopard skin—he and his wife, Florence Eldridge, came as a cave couple! David Niven opted for something a bit more sedate, looking very much like, well, David Niven.

Now that everyone’s seated for dinner, let’s scan the crowd… is that you tucked away in the corner?

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and usually a bit of backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

Finally! Maureen O’Hara Gets Her Oscar

Remembering the night the Academy finally honored Maureen O’Hara, with Liam Neeson and Clint Eastwood confessing lifelong crushes and Maureen looking skyward and calling to John Ford, “Pappy, we finally got an Oscar!” Thank God the Academy, at long last, did the right thing, and what an incredibly moving evening it was…

At last.

After more than 6o films in eight decades—and thousands of unforgettable moments—actress Maureen O’Hara finally received her Honorary Academy Award last night in Hollywood.

The 94-year-old actress was introduced by Liam Neeson and Clint Eastwood, who both admitted they’d been a bit in love with the Irish beauty since boyhood.

“I’ll never forget the moment… I was 12 years old at home, watching television on a rainy Sunday afternoon, and they were showing John Ford’s The Quiet Man,” recalled Neeson, clearly speaking from the heart. “The first time the Duke’s Sean Thornton saw her in that film was also the first moment I had laid eyes on her. His character had never seen beauty like that, and neither had I.

“For anyone anywhere around the world who loves movies, she is more than just an Irish movie star—she is one of the true legends of cinema,” he went on…

View original post 690 more words

Joan Fontaine’s Multi-Million-Dollar Legacy of Kindness to Animals

Joan Fontaine’s talent and beauty are legendary. But her kindness and grace, like the lady herself, were in a quieter key. She would take the time write back to every fan and honor any request she could, making all she wrote to feel as if they alone had captured her attention.

She also had a deep and abiding love of animals, especially dogs, whose faith and fidelity never failed her. She amply returned their devotion—and thanks to her spectacular generosity, many abused, neglected and abandoned animals have gotten a second chance at life, love and a home, which they might otherwise never have had.

The entire proceeds from Fontaine’s estate, which amounted to well over $1 million, and from the sale of her Carmel home, which sold for $2.6 million, benefited the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Monterey, California, where she adopted three of her own dogs, Kita, Fang IV and Samantha.

On what would have been her 98th birthday, and in honor of her incredible gift to animals, here’s a photo tribute to Joan with some of her own beloved companions (including Nicky, her terrier, who went just about everywhere with her):

THANK YOU, BEAUTIFUL JOAN, FOR EVERYTHING.

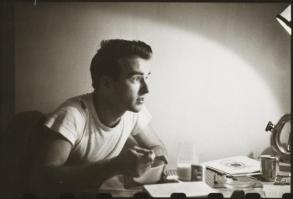

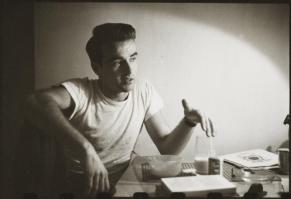

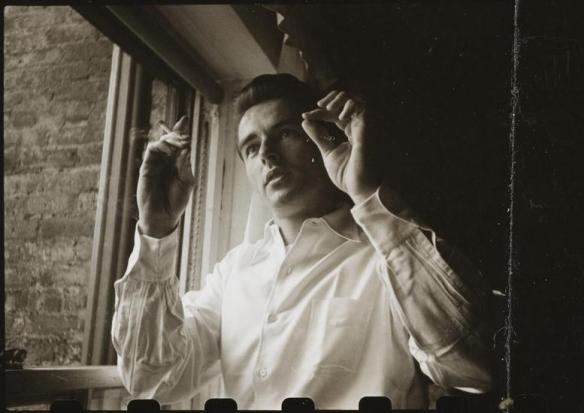

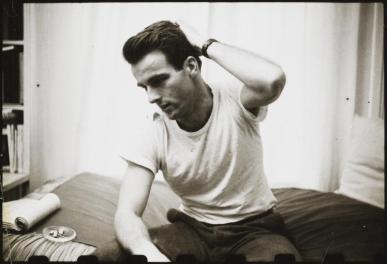

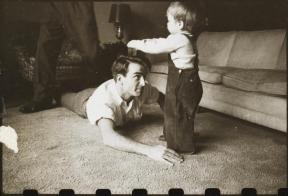

TINTYPE TUESDAY: At Home (and on the Floor) with Montgomery Clift!

Welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY! This week: a slightly early 95th-birthday tribute to Montgomery Clift.

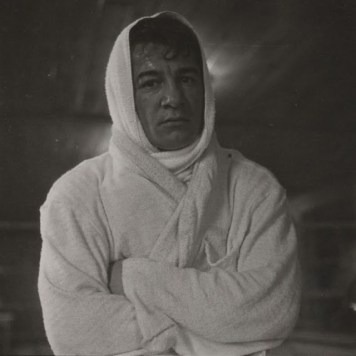

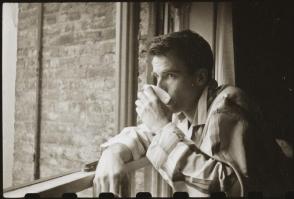

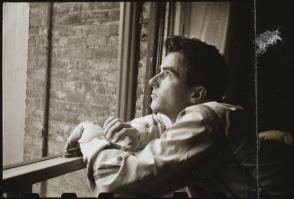

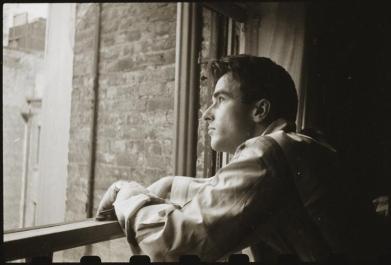

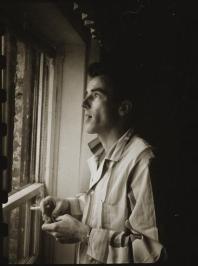

Before Stanley Kubrick began telling stories with moving pictures, he told them with still-lifes, as a $50-a-week photojournalist for Look magazine in the mid to late 1940s. Some of his early photo essays were staged (I know—you’re shocked!), but as he matured, so did his work. His subjects included boxers like Rocky Graziano, musicians like Frank Sinatra, actors, artists, and everyday New Yorkers.

In 1949, he was tapped to do a study of Montgomery Clift, who, after years of terrific work on the stage, was suddenly an “overnight success” in Hollywood.

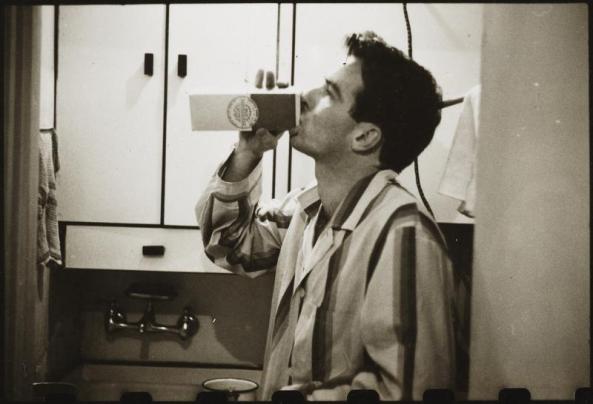

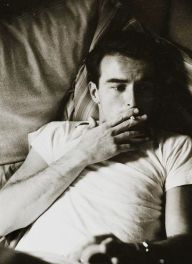

Earlier that year, Clift was nominated for a Best Actor Oscar in his first film, The Search; he was so natural, one reporter had asked director Fred Zinnemann, “Where did you find a soldier who could act so well?” Soon after, Red River (which had actually been filmed first) was released to raves, and The Heiress lay just ahead. But Kubrick, never one to put actors on pedestals, titled his photo essay “Glamour Boy in Baggy Pants.” He dropped by the actor’s Manhattan apartment earlier than expected—and the baggy pants he was met with were striped pajamas.

Would you scold him for drinking milk out of the carton?

Clift was completely comfortable with the camera…

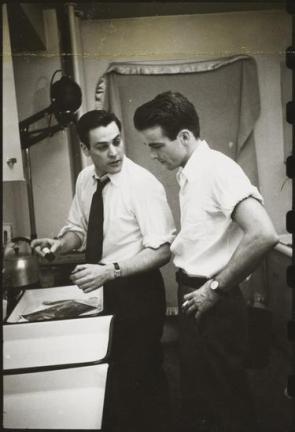

…but he loathed dealing with the media one on one. So for part of the shoot, he asked Kubrick to compromise and meet him at his friend Kevin McCarthy’s apartment. McCarthy was happy to run interference; an amateur photographer himself, he also showed off his kitchen-turned-darkroom. (Bonus points for the satin-piped blanket, a staple of every midcentury home, covering the door!)

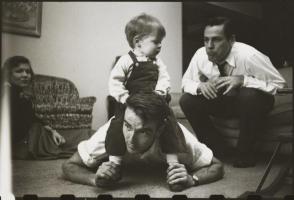

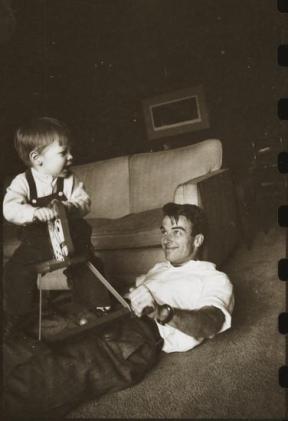

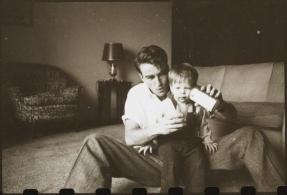

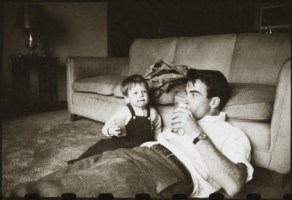

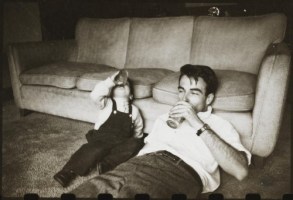

The two had grown close while working on Broadway in Chekov’s The Seal and later studied together at the Actors Studio. Clift spent many evenings with McCarthy and his wife, Augusta Dabney—usually ending up on the floor with their son, Flip.

“Monty was wonderful,” Dabney later remembered. “He made everyone feel special, everyone he met.” And some people felt free to walk, or ride, all over him…

…which is thirsty work.

McCarthy and Clift remained sporadically close for much of Clift’s brief life. In 1956, it was McCarthy who was driving the car in front of his friend, trying to guide him through the treacherous Hollywood Hills on that near-moonless spring night when Clift lost control and smashed his car into a telephone pole, shattering his face, his frame and his fragile psyche. He battled severe depression and addiction to painkillers for the scant 10 years that remained to him. “He was a terrific actor, a most charming and intelligent person, brilliant in every way,” McCarthy later recalled. “It was so awful the way his life deteriorated.” Mercifully, some photographs are sturdier than those they capture.

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and usually a bit of backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

Recent Comments