Remembering Billy Chapin, Who Saw Us Through THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER

More than half a century after shielding his little sister through the most monstrous night of their lives, John Harper left the world on her birthday.

Billy Chapin—who, as John, all but carried The Night of the Hunter on his slight shoulders—died on December 2, the day Sally Jane Bruce, who played Pearl, turned 68.

From the moment we meet him, it’s clear John Harper is an old soul, something his father Ben—a robber with a bullet in his shoulder and the law fast on his heels—is counting on. He stuffs $10,000 in stolen cash into Pearl’s doll and entrusts both the girl and the money to her brother:

From the moment we meet him, it’s clear John Harper is an old soul, something his father Ben—a robber with a bullet in his shoulder and the law fast on his heels—is counting on. He stuffs $10,000 in stolen cash into Pearl’s doll and entrusts both the girl and the money to her brother:

Ben: Listen to me, son, you gotta swear. Swear means promise. First, swear you’ll take care of little Pearl, guard her with your life, boy. Then swear you won’t never tell where the money’s hid, not even your Mom.

John: Yes Dad.

Ben: Do you understand?

John: Not even her?

Ben: You got common sense. She ain’t. When you grow up, that money’ll belong to you. Now stand up straight, look me in the eye. Raise your right hand. Now swear, “I’ll guard Pearl with my life.”

John: I will guard Pearl with my life.

Ben: And I won’t never tell about the money.

John: And I won’t never tell about the money.

Seconds after he gravely recites his vow, John is suddenly a child again for one brief, awful moment—almost doubling over in agony.as his father is knocked to the ground and dragged away in handcuffs.

But then he sets out to keep his promise, against what turn out to be nightmarish odds.

After Ben is hanged, his former cellmate—a self-styled preacher named Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum)—follows the missing money straight to John’s front door, quickly courting and winning his gullible mother, Willa (Shelley Winters) and his trusting sister—but never John, who realizes he must now try to protect not only Pearl but Willa as well.

Normally you wouldn’t give much for the chances of an 11-year-old boy against a six-foot-one psychopath—or for the chances of a child actor against the outsize Mitchum, in his best (and favorite) role. But even as Mitchum looms over him, swallowing him in his shadow, Chapin holds his own, and the screen. He conveys the deep seriousness of a child forced to grow up, or at least try to, in a matter of minutes, but he’s still so vulnerable it hurts. He pulls you so hard into his terrifying world that even if you’ve seen the film before, you’re knotted up in fear every time you watch it.

Normally you wouldn’t give much for the chances of an 11-year-old boy against a six-foot-one psychopath—or for the chances of a child actor against the outsize Mitchum, in his best (and favorite) role. But even as Mitchum looms over him, swallowing him in his shadow, Chapin holds his own, and the screen. He conveys the deep seriousness of a child forced to grow up, or at least try to, in a matter of minutes, but he’s still so vulnerable it hurts. He pulls you so hard into his terrifying world that even if you’ve seen the film before, you’re knotted up in fear every time you watch it.

At first, Powell tries to cajole the children into confiding in him about the hidden money. He’s so unnervingly persistent that even John—who’s developed more cunning than any child should have to—blurts out more than he ought:

John: You ain’t my Dad! You’ll never be my Dad!

Powell: When we get back, we’re all going to be friends and share our fortunes together, John.

John: (screaming) You think you can make me tell, but I won’t, I won’t, I won’t!

Horrified by the lapse in his defenses, he slaps his hand over his mouth to keep from revealing anything more. But it’s already too late: Powell now knows the money is somewhere in the house—and John knows where it is.

At this point, the hapless Willa is dispensible to her husband. After she disappears under the water, her throat slit wide and her blonde hair swaying like sea grass, John and Pearl are at the preacher’s mercy. And he hasn’t any.

Powell convinces the neighbors that Willa ran off with another man, but John knows better. And when the preacher hauls them to the table for another grilling about the money, John, his jaw set firm, all but wills Pearl to keep her mouth shut. But when she’s badgered to the point of tears, he can’t bear it. Playing for time, he says the money is buried under a stone in the fruit cellar. Powell grabs a candle and marches them downstairs ahead of him—only to discover the floor is solid concrete. Enraged, he throws John across a barrel and holds a switchblade to his throat: “The liar is an abomination before thine eyes!”

Terrified for her brother, Pearl screams, “It’s in my doll, it’s in my doll!” The preacher rears back and laughs, “The doll—why sure, the last place anyone would think to look!” Seizing on the brief distraction, John snuffs out the candle and knocks a shelf of preserves onto Powell’s head. Then he grabs Pearl, who’s clutching her doll, and pulls her up the stairs and out into the night.

In one of the most terrifying odysseys ever set to film, they run for the river, where John hopes to get help from his friend Birdie, who doesn’t trust Powell either. But after stumbling across Willa’s body while fishing, he’s drunk himself into oblivion in the barge house. (Moral of the movie so far: grown-ups are either useless or lethal.) With the preacher in pursuit, John drags out his father’s old skiff, shoves it off the shore and sets out with Pearl for… anywhere, as long as it puts distance between them and their homicidal hunter. And just as he pushes off, Powell plunges into the river, knife raised, letting go an ungodly shriek as his prey flee to the safety of the open water.

The river is their sanctuary, and for a few days they follow the currents, ever farther from what was once home, foraging or begging for food by the water’s edge and sleeping wherever they can, surrounded by nature both ominous and soothing. Some creatures are as vulnerable as they are, others are plotting a kill.

Finally, exhausted and hoping to find a soft place for the restless Pearl to lay her head, John steers the boat to shore, toward an old barn with an open hayloft. But just as he’s about to set his bone-weary body down, he hears the preacher hymn-singin’ in the distance, as the horse he stole lopes lazily along; he can take his time, he’ll catch up with them eventually. And with a mix of horror and heartsick resignation, John half-whispers:

“Don’t he never sleep?”

He quickly wakes his sister, bundles her back into the boat, and they return to the river. As the sun rises, their skiff drifts ashore, its young-but-old oarsman barely conscious and his sister fast asleep. They wake to see a wiry old woman hovering over them. “You two youngsters get up here to me this minute! Get on up to my house! Mind me now, I’ll get my switch!” Miss Cooper (Lillian Gish) barks. She’s already got a house full of cast-off children, and now “two more mouths to feed.”

Pearl takes to her immediately, but the battleworn John is still wary, and who can blame him? Still, she’ll turn out to be his savior—no man is a match for a Gish with a gun—and when she dispatches the preacher—who comes to claim “his children”—to the state troopers, John can almost believe he’s home at last. At Christmas, with no money or gift to give, he wraps an apple in a lace doily and shyly hands it to Miss Cooper. “That’s the richest gift a body could have,” she tells him, and he beams back at her. Now John is not only safe, but knows he’s safe. At last he, and we, can breathe.

About 10 or so years ago, UCLA devoted a special evening to The Night of the Hunter, including a panel hosted by Preston Neal Jones, author of Heaven & Hell to Play With, an oral history of the film. During the Q&A that followed, an audience member asked if anyone knew where the extraordinary Billy Chapin had disappeared to. Turns out he was in the audience. When Jones pointed him out, he stood briefly, acknowledged the waves of applause, and quickly slid back into his seat while everyone else was still standing, eager to escape the gaze of the crowd, however much affection it held for him.

You can only wonder how Chapin felt that night, seeing the boy up there on the screen, brutally robbed of his youth and almost his life. Like John Harper, his childhood was short-circuited, though in somewhat less monstrous fashion. He’d been acting almost since the day he was born—that’s him as the baby girl in Casanova Brown—but made just one more film after The Night of the Hunter, then did some television and fled the business at 15. Scant information is available after that, other than hints at a “troubled”life. He never talked publicly about his work, and in the acknowledgements for his book, Jones said Chapin “gave the project his blessing, although for personal reasons he was unable to participate.”

I hope when he returned home from UCLA that night, in the stillness of his solitude, he was able to realize how much he meant to people. And I wish, like John Harper, he could have found safe harbor. We all need a Miss Cooper. I wish, somewhere in this cold world, Billy Chapin had found his.

On the Anniversary of 9/11, Glimpses into Some of the Lives We Lost

The twin spirals of the World Trade Center made cameos in lots of movies, but this, I think, shows them at their best, reaching for the moon along with the lovers who glide past them. The towers show up around the two minute mark and linger a little in the night sky, before disappearing into the dark.

Today, of course, is the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. But it doesn’t feel like a “9/11” day in New York; it’s cloudier and cooler, and you can feel fall creeping in around the edges.

That morning in 2001, as I left for the subway, the sky was so clear and azure-blue that if you were a painter, you’d have added clouds just to break up the palette. The sun still felt reassuringly warm and summery, and made you feel like a fool for skulking underground to grab a train. I said out loud, to no one in particular, “What a perfect day!” It would’ve been a great day to play hooky, and I’m guessing some lucky souls saved their lives by doing just that.

Thousands of others left for work that morning, kissed someone they loved goodbye or maybe forgot to, and never came home. Of many, no trace has ever been found.

Until our company was acquired and some of us moved uptown, I worked as an editor in the upper floors of Two World Trade Center. At some point I’ll talk about what happened to me there, and the horrors I saw befall others, but for now I want to talk about the people I knew who were lost.

Joe, the maintenance man who took great care of everything and of us, often fell into the spare chair in my office at four in the afternoon or so, exhausted at the end of his shift, to complain about the ass-hat analysts who acted as if he was invisible until they needed something. He also had my back in any number of funny ways, as when he poked his head in, horrified, to say, “You work on files with these guys, right? Well, one of them just took one into the bathroom!”

Joe was still working in the towers on 9/11. He made it out of the building, but was hit by falling debris in the plaza.

Lindsay Herkness III, or the far less stuffy “Dinny” to his friends, was a senior VP at Morgan Stanley. The best way I can describe him is to tell you that he’d be played by George Sanders in a movie. Witty, charming, elegant—he seemed to have stepped out of another era. When we lunched together downstairs, he seemed like an alien presence in the dreary cafeteria, like a bon vivant who stops by at Christmas to give out plum puddings and presents. We had almost nothing in common except our love of old movies and dogs—mine a terrier mix I’d rescued from the street, his a basset named Beauregard Hound. But that was more than enough for us.

After the second plane tore through the South Tower on 9/11, Dinny remained calm. Too calm, as it turned out. He remained at his desk while his colleagues were ushered to safety, saying the towers were “the strongest buildings in the world.” But no building had ever had to endure this kind of hell. While his final, optimistic act cost him his life, I think it probably also helped those around him remain steady as they escaped with their lives.

The man responsible for getting the company’s staffers to safety was Rick Rescorla, a big Welsh bear of a man who was head of security when I started working there. At his insistence, safety and evacuation briefings were mandatory for all new employees. After calmly reminding us of the site’s history—it had already been hit by terrorists in 1993—he walked us through everything we needed to do to stay safe if it happened again. He was such an absolute brick that you felt like nothing bad could happen to you if he were by your side. Leaving the meeting, I told him it was the first time I ever felt safer after hearing someone talk about terrorism.

I never really liked working in the World Trade Center. On windy days, you could feel the building sway; it was the only place in New York where you could get motion sick at your desk. And I did feel there was sort of a bullseye on the whole place. But whenever I ran into Rick, genially patrolling the halls, I felt better.

After the North Tower was struck on 9/11, Port Authority security told those in the South Tower to stay put—that they were safer at their desks than in the chaotic plaza below. But Rick knew better. He grabbed a bullhorn and walkie-talkie and began systematically evacuating the thousands of people in his charge. Hundreds were in the stairwell when the second plane smashed into their building, which thudded and shook with terrifying intensity. He boosted morale by singing fight songs from his Cornish youth, also taking time to call and calm his wife: “Stop crying. I have to get these people out safely. If something happens to me, I want you to know I’ve never been happier.”

He was last seen headed up the stairs again as the South Tower collapsed.

I met Karol Ann Keasler only once, but that was enough to remember her always. Just before 9/11, my friend Amy introduced us when we ran into her at a downtown restaurant. She’d known Amy for years, but it seemed as if we’d both known her forever. She was warm and luminous and funny, and full of plans for her wedding in Italy. She’d only just come back from there, a week early, to help run an event for her company, Keefe Bruyette & Woods.

On the morning of 9/11, after the first tower was hit, Karol was on the phone with her mother in Arizona, assuring her that her building was safe and that she’d been advised to stay at her desk. Moments later, the line went silent as the second tower was struck. Karol and many of her colleagues were trapped above the flames.

There’s an old saying that in a mass tragedy, it’s not that a thousand people are killed, it’s that one person is killed a thousand times. I just wanted to share with you my memories of a few of the almost three thousand people killed 15 years ago today. Godspeed to all of them. And may none of us ever take it for granted when we and those we love make it safely home.

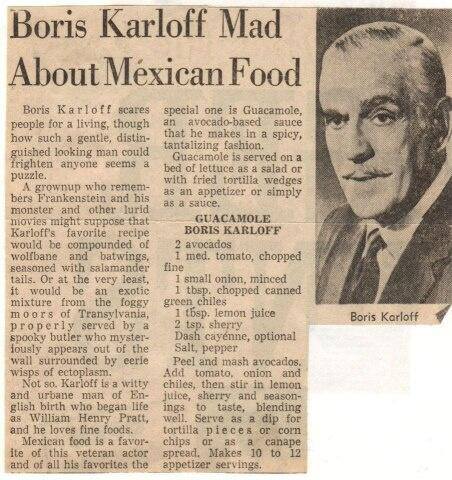

TINTYPE TUESDAY: The Ever-Elegant Boris Karloff—And His Secret Ingredient for Guacamole

Welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY!

Regular readers may recall just how very un-monstrous Boris Karloff was offscreen, visiting children’s hospitals to play Santa Claus and read bedtime stories—and even charming the little girl who played Maria in Frankenstein while bolted into full makeup. But can we talk for a minute about how insanely elegant he was?

He was the kind of guy who’d put sherry in his guacamole.

No really. I have proof.

Notice the cayenne is optional. The sherry isn’t.

And while most of us have to shlep to the grocer’s to make “avocado sauce”—and props to the reporter for describing guacamole as if it were an alien life form—Boris only had to head out to the backyard. He’d transformed his Beverly Hills estate into an earthly paradise—a sprawling, formal lawn ringed by lush flower beds and orchards dripping with oranges, grapefruit, lemons, limes, plums, peaches and yes, avocados. The only thing missing from his Eden were the apples and the snakes. And he tended his garden lovingly, every day, no matter what else he had going on.

“I’ll never forget, before we worked together in The Mask of Fu Manchu, during the summer we had a terrible drought,” co-star Charles Starrett once recalled. “Boris was making Frankenstein, and I lived above him in Coldwater Canyon. One evening, I was driving home when I suddenly nearly drove my car into a ditch—there in the beautiful garden was The Monster himself, tenderly watering the roses. Boris was such a dedicated gardener, he was afraid he’d lose the roses to the heat, so he rushed home without taking off his makeup to catch them at sundown, the best time for watering. It was quite a sight…”

His garden was such a heaven on earth that some of his friends longed to spend eternity there. “They loved to wander through the garden with Boris while he worked on it—they’d talk about their old times in the theatre,” remembered Karloff’s fourth wife, Dorothy. “They were very dependent on him when they were alive, and they loved the garden. That’s the way they wanted it—to be in a place they loved and to be near him… he felt it was his responsibility to do as they wished.”

Thus it came to be that the cremated remains of several of Boris’s oldest friends were buried among the roses behind his farmhouse. But Los Angeles real estate being what it is, a later owner subdivided the sacred space. Grieved Dorothy, “Pity they had to build all those ugly houses on top of them.”

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a regular feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and usually some backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss an edition?

Auntie Joan (Crawford) Explains It All for You!

Don’t say nothin’ bad about my Joanie.

Not long ago, in need of a tonic on a stifling summer day, I reread the closest thing we have to her autobiography, the wildly entertaining Joan Crawford: My Way of Life. On the cover, firmly gripping her pair of poodles, she looks like a terrified hostage trying to blink out a message to the cops. But the book itself is much more chipper, opening in her East Side penthouse:

“My home and my office are combined on a high floor of a Manhattan apartment house that has a cheerful California feeling about it, even in the winter. I get the first rays of the morning sun rising over the East River and, smog permitting, the last lovely colors of the sunset somewhere behind the Hudson. There are two small terraces where I try to keep some shrubbery going, and which my toy poodles adore, and I keep the rooms filled with plants and flowers. Even my dresses swarm with flowers. I have a bird’s eye view of the world here, and a bird’s sense of freedom. I have the same sense of excitement about the next adventure that I had when I was sixteen. And I’m sure I’ll never lose it.”

“All my nostalgia is for tomorrow—not for any yesterdays,” she tells us—and maybe she protests a little too much. But she’s trying, dammit—and Joan is all about the striving: “With a little organization, a woman can excel as a wife, a homemaker, mother, career woman and gracious hostess, be lovely to look at and be with—and still have time left over to be a good friend to a lot of people!”

For the love of God, ladies, don’t try this at home. Joan was pretty much the most organized woman on the face of the earth—a deeply unsettling childhood can send you hurtling in that direction—and even she bombed at some of these things.

Joan herself once admitted the book was a bit much. “I’m a God-damned image, not a person, and the poor girl who worked on it had to write about the image,” she confessed. “It must have been terrible for her. She would have been better off with Lassie.” (Am I the only one who just pictured Joan rescuing little Timmy from a well? And she would have done it in pearls and pumps, I tell ya!)

But not everything in the book is over the top, and, like your doting, slightly dotty aunt from Scarsdale who gives you aspic forks as a wedding gift, Joan always means well. Here’s a sampling of her advice: the good, the bad, and the—let’s face it—just plain odd.

The Good:

“I’ve persuaded myself that I hate things that are bad for me—fattening foods, late nights and loud, aggressive people head the list.” This is kinda genius. I’m off to shoot daggers at the brownies in the kitchen. (Though I bought them at a church bake sale, so I may have to go to confession later.)

“I never got over the idea that being on time was important.” Oh yeah, baby! “I am always on the set early,” she says. “When they ask me why I say, ‘I’m afraid you’ll start without me! Or replace me!'” She’s quick to say she’s joking, but I’ll bet she never entirely got over that feeling.

“Conquering fears, whatever they may be, opens life up.” Joan, for instance, was terrified of public speaking, flying, and horses, but made peace with them by learning more about them and facing down her anxieties. Granted, not all of us could vanquish our fear of horses by buying a fleet of polo ponies, but you get the idea.

“Before I go to bed at night, I make a little schedule for the next day.” Little schedule? She says her secretaries had to keep retyping her three-month calendar as she packed more and more into it. (Remember “retyping”?) And yet her New York assistant, Betty Barker—who joined her staff in 1938, after working for Howard Hughes—had plenty of options to bolt if she wanted to, and never did. So much for Joan being impossible to work with.

“In marriage, be a giver, not a taker.” Some may scoff at taking marriage advice from someone who made four trips down the aisle. But they’re just the people you should listen to: “People talk about what they want out of marriage. They should think about what you have to put into it. It’s worth every bit of love and protection and unselfishness you can muster up. And believe me, you can muster up much more than you thought you could before you were married.”

“No experience has ever made me bitter—or ever will.” That’s a bit hard to believe—she’s Joan Crawford, not Joan of Arc—but I think she means she didn’t stay bitter. After all, she kept up lifelong friendships with two of her ex-husbands, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Franchot Tone, even caring for Tone in her own home during the last months of his life. “When one lives with bitterness, it shows in the face, and it’s pathetic,” she says. “The softness goes out of the eyes. The body is stooped. Bitterness and self-pity are deadly poisons that can’t be hidden. They seem to exude from the pores.”

I think we can all relate to this, though perhaps on a humbler scale than La Crawford. In my case, there’s a clique of movie bloggers I call The Mean Girls (though one’s a guy) who are downright nasty to me; sadly, a few live nearby and I run into them once in a while. They’re all very chatty face to face, but what they say behind my back could curdle your custard. (Does that stuff ever not get back to people?) But since starting this site, I’ve met, in person and online, so many kindred spirits, they offset the mean ones a hundredfold. I’ll give Joan the last word: “You can’t be a giver if you’re bitter.”

Even in her infamous feud with Bette Davis, it always felt like most of the real rancor was coming from the other side of the fence. Joan seemed like the underdog, outgunned by Bette’s acid-laced attacks, which must have brought back horrid memories of childhood bullies:

“I worked my way through two private schools washing dishes, cooking for the entire establishment, making beds, waiting on tables—and trying to get some studying done in between. In the second school I was the only helper in a fourteen-room house accommodating thirty students and, in true Dickensian fashion, I was thrown down the stairs and beaten with a broom handle… that school didn’t teach me much out of books, but it certainly taught me to be self-sufficient, and I’ve never regretted it.” How many of us could glean a positive life lesson—or even pretend to—from being beaten and thrown down stairs? (And yes, those nightmarish years fueled an obsession with cleanliness and order, but that’s been dissected to bits all over the place.)

“I abhor dropper-inners.” Yes. Do not be one of these creatures! (Though nowadays it’s rare enough to get a real phone call, let alone a visitor.) Poor Joan recounts the time when not one but three dropper-inners descended on her New York flat, when she was wearing just “a simple cotton shift and very little makeup.” But our girl sprung into action: “I had to abandon everything, quickly run into my dressing room, get into a lovely dress I had bought in Canada, put on lipstick and tidy my hair.” (I know just how she feels: a while back, I was reading in bed in a teeshirt and skivvies when suddenly—horrors!—there was a knock at the door. I had to put on pants. I still shudder at the memory.)

Always pack in daylight. “In artificial light when I’m in a hurry it’s too easy to grab the wrong accessories and find myself in Kansas City or San Juan with a hot pink dress and a shocking pink hat—and that’s a catastrophe. Catastrophe. Oh my God.

For Joan, though, just getting her headgear out the door sounded like a job for the Navy SEALs: “My hats are stuffed with tissue, encased in plastic bags, and packed into large black drums that hold perhaps a dozen—drums about three feet high and almost too wide to get through the door of my apartment or into a car. But we always manage. And there is just no other way to transport lovely hats.” She once traveled to London with 37 suitcases. To film Trog.

And here’s a tip from Sister Celluloid: it’s also best to put on your makeup in natural light. In our house and maybe yours, there’s lots of “soft” lighting, which can make you look a helluva lot better than you really do—leading to something of a shock when you’re out from under its glow. (“But damn, I looked so good in the bathroom!”)

Joan’s five rules of thumb for choosing clothes. 1) Find your own style and have the courage to stick to it. 2) Choose your clothes for your way of life. 3) Make your wardrobe as versatile as an actress. It should be able to play many roles. 4) Find your happiest colors—the ones that make you feel good. 5) Care for your clothes like the good friends they are.

“A dress of the wrong shade will bring out sallowness, highlight blemishes, and add years to a woman’s face. It will make her look hard.” Preach it, Aunt Joan! I once fell in love with a gorgeous dress in a kind of mustardy yellow, and wore it to lunch with a friend—who said, before I even sat down, “Are you okay? You look ill.” And he kept at it all through the meal. (“Really? You’re sure you’re fine?”) When I got home, I took a better look in the mirror than I had before I left the house. It was the dress. I’m pale as milk—so much so that the muddy yellow in the dress reflected on my face. I looked like I’d been on a bender since 1962. Luckily, an olive-toned friend looked great in it.

The Bad:

“Once girls get themselves married, they forget romance—and that’s when the flirting should really begin. If you want to keep your husband, that is. A lot of other women are flirting with him and flattering him—you can depend on that.” Okay whoa. This reminds me of that noxious little ditty from the ’60s, Wives and Lovers. When Jack Jones starts crooning, “Hey, little girl, comb your hair, fix your makeup…” I want to scream, “Hey, little man, feck off!”

Of course everyone should keep kindling the romantic fires and making that extra effort after marriage. But Joan’s advice is a bit one-sided… and the idea that the minute you let your lipstick fade, your husband is going to hop into bed with some cutie from the office is downright creepy. And it’s disappointingly dated, coming from a woman who always seemed so far ahead of the curve.

“Don’t buy a dress until you can afford all the right accessories and have a hat made to match.” Okay so most of us will go around wearing barrels for the rest of our lives.

“Pants are probably here to stay. But they shouldn’t stay long on anyone but the most lithe and slim-hipped.” The next sound you’d hear would be most of my clothes hitting the charity bins.

“A busy woman can’t spend whole days in front of mirrors, but she ought to have them all over the house (which improves the décor too) and make a point of glancing at herself every time she passes one.” Oh dear God no. Including the décor part. It would be like living in a giant ladies’ room.

The Odd:

Her “dangerous” foods. “Here are a few items no dieter should ever have in the house: peas, lima beans, avocados, olives, dried beans, corn, butter, most cheese, fatty meats, sugar, chocolate, potatoes, rice, bread, pasta, and creamed soups. The list could go on for another page or two, but any intelligent woman knows the dangerous foods.”

Butter, cheese, meats, sugar—check. But this is the first time I’ve ever heard anyone demonize the sainted avocado. And peas, beans and olives? What did they ever do to hurt anyone?

Meanwhile, her chapter on entertaining contains enough bacon, meatballs, fried chicken, sausage, salami, steak, butter and mayo to choke a horse. I guess the best way to stay slim is to fob off all that stuff on your unsuspecting guests.

“Bedrooms should be very feminine.” Joan says “men feel much more masculine walking from a brown or green dressing room into a lovely feminine bedroom.” I polled my husband and a few male friends on this one. The consensus? Five said no, with any number of ribald expletives thrown in for good measure, and one spewed coffee out of his nose. And none could recall having a dressing room—brown, green or otherwise.

“A turquoise necklace with amethyst earrings is a crime.” Not a fashion misstep, mind you. A crime. I love this woman. (And let me confess that I have a necklace with both amethyst and turquoise stones in it. But please don’t turn me in—my dog depends on me!)

“Sit on hard chairs—soft ones spread the hips.” I’m pretty sure this is an old wives’ tale. Old wives who were really cranky and crying out for cushions.

Use every free second to exercise. Joan was always in wicked-good shape, so it’s hard to quibble with her on this one. But she goes on for pages and pages about working exercise into pretty much every minute of your life. Clench your buttocks in the grocery line! Firm your calves while you brush your teeth! Do odd, scary facial exercises that creep out your taxi driver! If your muscles are relaxed for a single second, you’re living your life all wrong.

I mean, please. Not all of us can slink into leotards at lunchtime and work out with our poodles, as she did during the stinker Torch Song.

But then, not all of us can be Joan Crawford. Rereading this somewhat frantic book, I can’t say I’d want to be. But I’d love to have been her friend—and I’ll bet she’d have been a damn good one back.

THE NITRATE PICTURE SHOW: When the Screen Glistened with Real Silver

There’s a reason they call it the Silver Screen.

In the early days, reels of nitrate film contained actual silver. Most of these precious spools were melted down by studios for their metal content or neglected until they turned to dust, liquefied or burned in warehouse fires.

But not all are lost—and earlier this month, the passionate film-preservation team at the George Eastman Museum painstakingly culled prints from archives around the world for the second Nitrate Picture Show in Rochester, New York.

Sneaking away for a brief weekend, I rode past the sprawling old mansions on East Avenue, slid into my seat at the Dryden Theater, and slipped into silvery heaven. Suddenly I was no longer covering classic movies—I was actually back there, when they were new.

And gorgeous.

This year’s offerings included Otto Preminger’s Laura, Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief, John Boulting’s Brighton Rock, George Sidney’s Annie Get Your Gun, the Library of Congress’s print of Powell-Pressburger’s Tales of Hoffmann, Martin Scorsese’s personal copy of David Lean’s Blithe Spirit…

…and Jean Negulesco’s noir classic, Road House. Because waking up to Richard Widmark at 10:00 on Sunday morning is my idea of church. Even if he is vaguely homicidal. In this typically stunning nitrate print, when he was lurking in the background as Ida Lupino purred her smoky vocals, he actually was in the background, so multi-layered and deep were the images.

The final film of the weekend—the Blind Date with Nitrate, not revealed until it appeared onscreen—was Edwin Carewe’s 1928 version of Ramona , starring Dolores del Rio as the put-upon heroine and Warner Baxter as the head of a Native American sheep shearing team. (I kept waiting for him to say, “You’re going to go out there a lowly sheep shearer, but you’ve got to come back a star!”) Del Rio was at her most luminous, and the print reflected the kind of yeoman’s effort the Eastman staff puts into tracking down films: it was a German copy of an American movie unearthed from a Russian archive, where it had resided since Soviet film scholar Georgii Avenarius brought it home as a “trophy” after World War II.

Before I headed home, projectionist Ben Tucker gave me a tour of the booth, which is clearly his second home. The closed-head projectors—which keep the film safely tucked inside—were installed when the theatre opened in 1951; valves and shutters protect the highly flammable nitrate reels from the hot beams of light that could ignite them if they stop rolling for even a second. “If the film so much as slows down, I have to flip a dowel to cut off the heat source,” Tucker said, shuddering at the prospect.

That love of film and the deep desire to protect it ran through the whole weekend like a gentle but constantly humming current. This may be the most civilized film festival I’ve ever attended—but not in a raised-pinky sort of way. There was no pushing, no shoving, no “look at me” types, no rushing around. It was like wandering into a big old house on a hill after a long journey, and discovering hundreds of people from all over the world who are of like mind and heart. You may never have been here before, but you’re home.

And no one is trying to sell you anything—though the museum does have a gift shop full of film fare at much-too-tempting prices. (When I teased her about the store being dangerous, the checkout woman said, “I know! I think the only reason they keep me on staff is because I buy so much!”)

The one troubling aspect of the whole festival? There’s no “Annual” in its name. It’s like falling in love on a first date and then agonizing over whether he’s going to call you again.

But mercifully, they’ve already announced that the third Nitrate Picture Show will be held next year on May 5th through 7th.

See you there.

When Richard Widmark Hugs You, You Stay Hugged

Back in the spring of 2001, the Walter Reade Theatre had a retrospective of Richard Widmark films, with a special—to put it mildly—appearance by the man himself, who was then 86.

I had loved Richard Widmark since I was a kid, when I saw him in Don’t Bother to Knock. He seemed like a bit of a heel at first, but there was something about him—something that told me a very fragile, deeply disturbed Marilyn Monroe would be safe with him. (She was—on and off the screen.) I hadn’t yet seen him push Mildred Dunnock down a flight of stairs in her wheelchair—which, he once recalled, was the first scene he ever shot on film after making the move from Broadway to Hollywood. (“I said to Henry Hathaway, ‘You want me to do what?'”) But by then I already adored him. (Poor Tommy Udo, I thought—so misunderstood!)

So off I went to the theatre, clutching my then-fiancé (now long-suffering husband) Tim with one hand and my fan letter with the other. It went on for about four pages but mostly said “I LOVE YOUUUUUUUUUUU!” (It was all very sophisticated, I tells ya.)

We got there nice and early and sat right on the aisle; I figured when he passed by on his way to the stage, I could give the letter to him or whoever was with him. In my excitement, it took a while for it to dawn on me that—duh—there’s an aisle on either side of the theatre, and he could just as easily go up the other one.

So I scrambled to the lobby to give the letter to somebody, anybody. But then—wham bang sigh faint—there he was. Fans were sort of swarming him. One galoot ran up, stood next to him, handed his friend a camera for a picture, and then scampered away, without saying a word. Like he was posing next to Stonehenge instead of an actual human being. Others were kind of chewing his ear off and monopolizing him, but he was very gracious about it, nodding, smiling, not getting a word in, not seeming to mind. He was clearly used to it, God help him. Most of them looked kind of like this (and yes, some actual berets were present):

One especially gaseous fan (I’m sure he’d prefer cinephile) asked a question that seemed designed to cram everything he knew about film into one five-minute ramble, which boiled down to, “Why didn’t you ever direct?” After seeming a little startled that the guy had actually stopped talking, Widmark smiled, trained his clear-eyed gaze on him, and answered in eight words: “I didn’t want to get up that early.”

Sensing he was just about ready to bolt, I started to panic. My usual instinct in these situations is to flee, ceding the floor to the pushy, squeaky wheels. But not this time. I had to give him that letter. So I sort of wriggled into the crowd, and suddenly there he was, right in front of me, beaming a lovely smile, his blue-gray eyes sparkling. I handed him the letter and said something like, “Mr. Widmark, I knew you’d be very busy with everyone wanting to see you, so I just wrote a few things down, to say how much you mean to me.” Only I think it sounded more like, “Aaaaauuuughoooouuuhhaaaaahuuuuuhooooh.”

And he stepped forward out of the horde and hugged me hard and said, “That’s wonderful!” A warm wave of current swept through me, short-circuiting my limbs and making me so wobbly I was sort of weaving. Hoping I could make a semi-graceful exit that wouldn’t leave me in a heap on the sticky lobby floor, I said thank you or I love you or something and staggered back to my seat, cursing my knees for lack of support.

Tim took one look at me and said dryly, “I guess you found him.”

About a week later, I opened my mailbox to find a lovely cream-colored envelope, in gorgeous, exuberant handwriting, postmarked Roxbury, Connecticut, where I knew he lived. I leaned against the wall in the lobby, held my breath, and opened it. It was from him. I slid down the wall and sat on the floor, and my neighbors, coming home from work, were like, “Uh, are you okay? Should we call someone?” I was fine. Beyond fine. In the letter, he thanked me for my very kind (underlined) words. And I thought, no, not kind. Just true. And not nearly enough words to describe how wonderful he was.

While writing this tonight, I looked up the dates for that film festival; the night we saw Richard Widmark was the first Saturday of the series. It was May 19. Exactly 15 years ago today.

It seems this man will never stop giving me chills.

P.S.: I have stayed hugged.

A Film Noir Feast! TOO LATE FOR TEARS and WOMAN ON THE RUN Are Gorgeously Restored on DVD

A double dose of classic noir has just hit the DVD shelves.

Two lost gems, Too Late for Tears and Woman on the Run, have been restored to their dark and gorgeous glory by the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The DVD sets—which include standard and Blu-ray discs as well as tons of special features—mark the first of what I hope are many collaborations between the Film Noir Foundation (FNF) and Flicker Alley.

Byron Haskin’s Too Late for Tears opens with a startling sight: an almost timid Lizabeth Scott.

When first we meet Alan and Jane Palmer (Arthur Kennedy and Scott), they’re on their way to a party, but she’s begging him to turn the car around—fearing she’ll be the brunt of condescending comments from the hostess, “looking down her nose at me like a big, ugly house up there looks down its nose on Hollywood.”

When Alan finally relents and pulls over, a driver heading in the other direction mistakes him for a blackmailer he was due to meet, and tosses a bag of hot money into the back seat of their car. Alan is troubled, but Jane is practically vibrating with excitement—grabbing the wheel and going from zero to moll in 1.5 seconds, screeching and careening down the highway like Bonnie Parker’s blonder sister. When a cop stops them for speeding, she’s already going for the gun in the glove box until she realizes he’s not a threat. (And God help anyone who is.)

But if she’s a little fast, hubby’s a little slow. She wants to keep the cash, he wants to turn it over to the cops.

“What is it, Jane? I just don’t understand you,” he understates wildly. “I’ve tried to give you everything… everything I could.”

“You’ve given me a dozen down payments and installments for the rest of our lives,” she spits back.

Ouch.

But he still tries to pull her over to the side of the angels: “The only thing worth having is peace of mind, and money can’t buy that.” Hey buddy, have you actually met your wife?

The next day, while Alan’s at work, the actual blackmailer, Danny Fuller, drops by in the person of—who else?—Dan Duryea. He sizes her up as a schemer right away, but knows he needs her help to get the money. What he doesn’t know is how far she’ll go to keep it.

Danny threatens Jane (“I hope for your sake, beautiful, you’re not trying to soft-soap me—I wouldn’t take kindly to it”) and even roughs her up a little, but it’s clear she’s calling the shots—and not just because she’s got the cash. She’s also got the stomach for just about anything, and he hasn’t. (You know you’re wicked when Dan Duryea is the voice of morality.)

Danny’s shocked at just how venal Jane is—and just how much he wants her. (“Don’t ever change, tiger. I don’t think I’d like you with a heart.”) When she drags him down into her moral sewer, his self-loathing and self-awareness meet somewhere in the middle. And it’s actually pretty heartbreaking. (“This gave him more room to create a character with a little sympathy… he was conflicted inside,” Duryea’s son Richard says in one of the terrific bonus features on the DVD.)

Even Jane is a bit taken aback by the dirty deeds she has to pull off—Why do people keep making me kill them?—but she gets over it in a hurry.

When Alan disappears, though, she has some explaining to do. Hot, or maybe lukewarm, on her trail are Alan’s doting sister Kathy (Kristine Miller)—a would-be mother-in-law who lives across the hall—and Don Blake (Don Defore), who claims to be Alan’s old war buddy. When these human speed bumps sidled onto the screen during the film’s original run, I’m guessing they caused a stampede to the concession stands, much as when Alan Jones started warbling arias in A Night at the Opera.

Soon we discover that Don may or may not be all he seemzzzzzzz… Oops sorry, I’m back now. Kathy and Don are just about the worst argument ever for staying on the straight and narrow. Crime may not pay, but at least it keeps you awake. And when they bundle into their little love scene, it’s just… sad. Especially after we’ve seen Dan Duryea pretty much swallow the lower half of Lizabeth Scott’s face. (That thudding sound you hear is a woozy Breen Office censor hitting the floor.)

I won’t give anything else away; you really should see this beautiful new print for yourself, even—or maybe especially—if you’ve seen the muddy mess currently out there in the public domain. Bonus materials include a terrific commentary track by FNF film historian Alan Rode (who also wrote a brilliant bio of noir icon Charles McGraw); a mini-doc with insights from Rode, Richard Duryea, FNF founder Eddie Muller, Julie Kirgo and Kim Morgan; a fascinating feature about the film’s restoration; and a souvenir booklet with poster art, rare photographs, lobby cards and a sharp essay by film historian Brian Light.

Woman on the Run was even more in need of rescue than Too Late for Tears, and was actually thought to be lost—twice.

When Muller first fell in love with the film, the only copies he could find were scratchy VHS tapes. But finally a colleague, Gwen Deglise at American Cinemateque, unearthed an agreement between Fidelity Pictures, the producer, and Universal, the distributor, which required Universal to maintain a copy—and after a bit of digging, the studio found it. When Muller screened the print at the Castro Theatre in 2003, the original tape was still on the reels—it had never been shown before.

Fast-forward five years, when a studio welder left his torch unattended, starting a blaze that wiped out a heartbreakingly large swath of the Universal lot—where the only copy of Woman on the Run was stored. (It seems fitting to form a torch-wielding mob to get this guy… Who’s with me, kids?!?) So… how on earth do we have a pristine print today? In an act of noble piracy, Muller had made a copy of the film, unable to bear the thought that there was only one in existence—one that would soon be out of his hands.

I first saw the restored print—which got a funding boost from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association’s Charitable Trust—at the Los Angeles Noir City festival last spring, before I’d ever even heard of the movie. (That’s the great thing about Muller and company: you always learn something new. You feel like kind of an idiot around them, but in a good way.) I instantly fell in love and couldn’t wait for it to come out on DVD. Now the wait is over—for noir fans and for Ann Sheridan, who poured her heart, soul and money into the film and wound up with little to show for it.

Sheridan co-produced Woman on the Run not long after buying out her contract from Warner Bros., where they strapped her into a series of ever-tighter sweaters and dubbed her the Oomph Girl—a nickname she detested. (“‘Oomph’ is what a fat man says when he leans over to tie his shoelace in a phone booth.”) She stars as Eleanor Johnson, a bitter, jaded wife whose husband Frank (Ross Elliott) goes on the lam after witnessing a gangland slaying. This turns out to be the best thing that ever happened to their miserable marriage.

When an inspector (Robert Keith) arrives at the murder scene, he asks Frank if he’s married. “In a way,” he mutters half-heartedly. And that’s actually more enthusiastic than his wife is when the cops show up at their dingy flat, where the only sign of domesticity is a cupboard full of Ken-L Ration. (Like a lot of depressives, they may have given up on their marriage, their lives and themselves, but dammit, they take care of their dog.)

When Frank calls, Eleanor warns him that the police are tapping the line, so he hangs up and hits the road. But she soon learns from the cops—everyone seems to know more about her husband than she does—that he needs heart medicine he may not be able to survive without.

As Eleanor scours San Francisco in search of Frank, she discovers facets of his life she’d never known about: He went to the mat with his boss to save a friend’s job. He inspired a massive crush in a young secretary. He lived like Gaugin in Tahiti and Hemingway in Mexico. And he still loves his wife. That last bit of news comes as a something of a welcome shock to Eleanor. When the inspector tells her that a letter Frank wrote “sounds like a man in love,” she’s knocked a bit backwards with relief—almost allowing herself to feel hopeful. Then she leans in for a closer listen, as if she needs to hear it again.

Helping her on her quest to find her husband is noir regular Dennis O’Keefe as an obnoxious-but-charming reporter eager to snag an exclusive (and maybe Eleanor in the bargain). Sheridan has a crackly chemistry with him and with Keith, who seems to have been born craggy.

The whip-smart, cynically romantic script was written by Alan Campbell with an assist from director Norman Foster, who soaked up everything he could about mood, light and shadow from his mentor, Orson Welles. (Foster’s Journey Into Fear, featuring Welles, was so effective that Welles had to reassure skeptics he didn’t direct it himself.)

Campbell knew a thing or two about brittle, wearily witty women, having recently divorced Dorothy Parker. (They remarried after this film; movie as couples therapy?) And Foster endured a rather… complicated marriage to Claudette Colbert (she lived with her mother, he lived alone).

Anyone else notice more than a passing resemblance between Foster and the guy he chose to play the husband?

Woman on the Run is lovingly shot all over San Francisco, which almost becomes another character in the film. And this isn’t Hitchcock’s glistening city by the bay: it’s docks and dives and dime stores, with the occasional edifying bit of architecture thrown in for good measure. (City Hall doubles as an art gallery.) The film climaxes with a harrowing chase through a spooky seaside amusement park (its one faithless locale; logistics dictated that they shoot in Santa Monica).

Even The New York Times‘ Bosley Crowther liked the film, kinda: “Since it never pretends to be more than it is, Woman on the Run… is melodrama of solid if not spectacular proportions. Working on what obviously was a modest budget, its independent producers may not have achieved a superior chase in this yarn about the search by the police and the fugitive’s wife for a missing witness to a gangland killing. But as a combination of sincere characterizations, plausible dialogue, suspense and the added documentary attribute of a scenic tour through San Francisco, Woman on the Run may be set several notches above the usual cops-and-corpses contributions from the Coast … will not win prizes but does make crime enjoyable.”

As usual with Crowther’s work, you’re tempted to write “he sniffed” at the end. As best I can figure, there used to be some kind of annual prize for Most Condescending Review, and he was determined to snag it every year running. Trust me, you’ll like Woman on the Run, in this great new print, much more than he did.

Bonus features include audio commentary by Muller (whose love for the film comes through in every syllable) as well as his essay about its rediscovery and rescue; a mini-doc about the restoration; another about the film, with the same folks who are on Too Late for Tears; a virtual tour of its San Francisco haunts; a short film about the Noir City festival; and a souvenir booklet that includes lobby cards, rare stills, and a not quite accurate but still fabulous map of movie locales, which was sent to distributors.

If you love movies—whether or not you’re a hard-core noir fan—snap up these two beautiful, thoughtfully presented DVD sets as fast as your fingers can carry you to Flicker Alley.

Recent Comments