TINTYPE TUESDAY: Ann Miller, Ginger Rogers, Lucille Ball and Judy Garland Hit the Town to Do the Charleston!

Welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY!

You’re Ann Miller. You’ve been hoofin’ your heart out all day long, and your dogs are barkin’ like there’s someone at the door. It’s a lovely spring night in Hollywood—perfect for parking your tired tootsies on a nice warm veranda somewhere. So what do you do?

You call up your friend Ginger and you say, “Let’s go dancing!”

Meanwhile, Lucy is phoning Judy with the same idea…

The Mocambo—once Hollywood’s most glamorous nightclub—hosted a Charleston contest every Monday night. And pity the poor, hopeful couples who strapped on their dancing shoes and showed up on May 13, 1950, only to find themselves flat up against…

and…

Could it get any more fabulous than this? I’m so glad you asked! You see the band behind them—the guys in the fireman’s helmets? They’re animators, musicians and writers from Walt Disney’s studio, who used to jam along to jazz records on their lunch break. Then one fateful day, the phonograph broke, and they realized they were good enough to go it alone—and hey, kids, they started a band!

The only cheap vehicle they could find that was big enough to haul them and their instruments was an old 1914 fire truck. So bandleader/trombonist Ward Kimball (one of Disney’s “Nine Old Men,” his key animators) went out and hunted down genuine helmets and uniform shirts to complete the theme, and called the band Firehouse Five Plus Two. (The “plus two” were a trumpeter and banjo player who joined shortly afterward.)

The group played together from 1949 to 1972, recording 13 albums—but they never gave up their day jobs.

So get in the car, kids, we’re goin’ dancin’!

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

STREAMING SATURDAY! Melvyn Douglas and Burgess Meredith Give Merle Oberon THAT UNCERTAIN FEELING

Welcome to another edition of Streaming Saturdays, where we embed a free, fabulous film for you to watch right here every week!

Settling in to watch That Uncertain Feeling, there are some things you can be certain of. With Ernst Lubitsch at the helm, you know it’ll be witty and sophisticated. And you assume Melvyn Douglas will elegantly knock your socks off, while Burgess Meredith will be quirkily brilliant.

You know what you don’t necessarily expect? Merle Oberon to be hilarious. But she is.

Oberon plays Jill Baker, the wife of a career-crazed insurance executive (Douglas)—and when he regales her with tales of his actuarial conquests, her eyes somehow manage to flash stupefying boredom and blinding rage at the same time. Her husband’s lack of attention to anything but business—he’s much more interested in wooing Hungarian mattress salesmen than winning his wife—drives Jill to develop a recurring case of hiccups so forceful they send her tiny frame flying backwards, as if she’s been struck by a bullet. And she can’t shake them off for love or sugar cubes.

So Jill heads off to an analyst (the delicious Alan Mowbray) in search of a cure. But it’s in his waiting room where she thinks she’s found the real answer to her problems: an idiosyncratic concert pianist (Meredith) who’s convinced he’s too brilliant for any of the philistines around him to appreciate. (“I’m against anything and anybody—I hate my fellow man and he hates me!”) Ah, but she understands him…

I’ll say no more; with Lubitsch in the driver’s seat, you really just need to sit back and go where the movie takes you.

My only qualm about the whole affair is that Baker’s secretary (Eve Arden), who’s crazy about her boss and fed up with his wife, gets caught in the middle of the love quadrangle. (Would it have killed Hollywood to realize that the funny, whip-smart and by the way gorgeous Arden deserved to get the guy a little more often and get kicked around a little less?)

Oberon, who did far too few comedies, remembered That Uncertain Feeling as “the happiest picture I ever made.” Even if she already had a clear idea of how to do a scene, she always asked Lubitsch to demonstrate it first, because he was so outrageous.

“I don’t know when I had a better time in my whole career than during that period,” Meredith agreed. “He’d act everything out for you because he loved the part, and he’d act it out so funny, so definitely, that I’d stand there as an audience… he would give you the idea of what he wanted, and he would stop in the middle of acting my lines and make some crack about my brother, who I was having trouble with then, or some purely personal thing, which in some psychic way he knew I was undergoing. He was a very psychic man. And he knew I’d come over and say, ‘How did you know about that?’ and he’d say, ‘I have ways of knowing!'”

Douglas was also thrilled to be re-teamed with Lubitsch and Ninotchka writer Walter Reisch (who would go on to pen a little number called Gaslight). Reisch’s collaborator on That Uncertain Feeling was Donald Ogden Stewart, who’d adapted The Philadephia Story, co-written Dinner at Eight and Kitty Foyle, and written Holiday and Love Affair.

And yet here it is, languishing in the public domain. What’s a fabulous Lubitsch movie doing in a place like this? Credit the lunkheaded movie audiences of 1941. The director formed his own company to produce the film—but just as quickly dissolved it when it bombed, losing more than a quarter of a million dollars. So the copyright on the now-orphaned movie was never renewed.

STREAMING SATURDAYS is a regular feature on Sister Celluloid, bringing you a free, fabulous film every weekend! You can catch up on movies you may have missed by clicking here! And why not bookmark the page to make sure you never miss another?

One of Alan Rickman’s Last Roles Is Saving Lives—And You Can Help

We all woke up to awful, heartbreaking news this morning. Is there anyone who didn’t love this man in something, or ten or twenty things? Reading just some of the tributes from his friends and colleagues, I was struck by how they were so much deeper than the usual “great talent… thoughts and prayers with his family” stuff. Alan Rickman was much more than a brilliant actor; he was a kind, loyal, wonderful man who was deeply loved.

One of the last projects he donated his time and his incredible voice to was a video to aid refugees, but, typically, he does it in a very droll way. And all you need to do to help is to click on it. Obviously if you are in a position to send along a donation to Save the Children or the Refugee Council, that would be great. But just clicking on the video helps. Think of it as your personal tribute to an amazingly gifted, compassionate man who gave so much to his fans and friends, and who left a lasting mark on the world.

If I embed the video, it won’t count as a “view” on YouTube, so here’s the link to paste into your browser: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HkiMz-e2ZcE

Please also share the link with your friends.

Godspeed, wonderful Alan. And thank you for everything.

“A film, a piece of theatre, a piece of music or a book can make a difference.

It can change the world.”

TINTYPE TUESDAY: Teresa Wright, the Anti-Pin-Up Girl

Welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY!

We’ve all heard of unusual clauses in actors’ contracts. But Teresa Wright’s—written when she was just starting out at 23—takes the cake. (And that cake does not have a scantily clad starlet popping out of it):

The aforementioned Teresa Wright shall not be required to pose for photographs in a bathing suit unless she is in the water. Neither may she be photographed running on the beach with her hair flying in the wind. Nor may she pose in any of the following situations: In shorts, playing with a cocker spaniel; digging in a garden; whipping up a meal; attired in firecrackers and holding skyrockets for the Fourth of July; looking insinuatingly at a turkey for Thanksgiving; wearing a bunny cap with long ears for Easter; twinkling on prop snow in a skiing outfit while a fan blows her scarf; assuming an athletic stance while pretending to hit something with a bow and arrow.

In short, Miss Wright had already seen enough—apparently including every campy pin-up shot ever published. But she managed to be both indignant and hilarious about it. (With a wit like that, it’s no wonder writers loved her; she married Niven Busch and Robert Anderson.)

While Wright managed to escape the bunny ears and bathing suits, she was held hostage for at least a couple of semi-cheesecake sessions. And judging from the look on her face, the ransom couldn’t be paid fast enough:

Wright earned Oscar nods for her first three films—The Little Foxes, Mrs. Miniver and The Pride of the Yankees—taking home the trophy for Mrs. Miniver. Even her Academy Award was unglamorous—made of painted plaster, as metals were set aside for the war effort. (And today, most actresses wear more makeup in the shower than she wore to the ceremony.)

Wright followed up with films like Shadow of a Doubt and The Best Years of Our Lives—confiding to friends that in William Wyler’s post-war drama, she was thrilled to finally shed her wholesome image and play an aspiring homewrecker. But even then, she led with her heart, trying to rescue the man she loved from a viper. Damning her with the kind of faint praise she didn’t deserve, Wyler called her “the best cryer in the business.” Her boss, producer Sam Goldwyn, agreed—and kept casting her as dewy, vulnerable young lovelies. (This was the same man who once barked to her, during filming on The Little Foxes, “Teresa, let your breasts flow in the breeze!”)

In 1948, Wright—now a 30-year-old mother of two—was once again cast as an innocent waif, this time complete with an evil stepsister. And while she was unhappy with Enchantment, the critics weren’t. Newsweek said she “glows as the Cinderella who captivated three men,” while The New York Times said she “plays with that breathless, bright-eyed rapture which she so remarkably commands.” Tired of glowing breathlessly, Wright declined to embark on a long publicity tour for the film—leading Goldwyn to cancel her $5,000-a-week contract and publicly criticize her as “uncooperative.”

Wright responded:

I would like to say that I never refused to perform the services required of me; I was unable to perform them because of ill health. I accept Mr. Goldwyn’s termination of my contract without protest—in fact, with relief. The types of contracts standardized in the motion picture industry between players and producers are archaic in form and absurd in concept. I am determined never to set my name to another one… I have worked for Mr. Goldwyn seven years because I consider him a great producer, and he has paid me well, but in the future I shall gladly work for less if by doing so I can retain my hold upon the common decencies without which the most glorified job becomes intolerable.

Wright went on to have a much more interesting and varied, if lesser-paying, career than Goldwyn had in mind for her—working with Matt Damon almost fifty years after she co-starred with Marlon Brando. And she never lost her sense of humor. “I was going to be Joan of Arc,” she once noted wryly, “and all I proved was that I was an actress who would work for less money.” But with much more integrity.

“I only ever wanted to be an actress, not a star,” Wright once said. But her Mrs. Miniver co-star Greer Garson saw it as inevitable, whether she sought it or not: “Very bright. Fantastically beautiful. Very much the lady. She was a great Irish wit. There are actors who work in movies. And then there are movie stars. She was a movie star.”

Here’s to Teresa Wright, who was so radiantly gifted, honest and genuine you almost forgot she was gorgeous. She wouldn’t have had it any other way.

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

TINTYPE TUESDAY: Start the New Year Right with Gloria Swanson!

Happy New Year, my dear friends! And welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY!

Need a little help making this year a bit healthier than the last? Sure, you could turn to a personal trainer or a gym coach. But wouldn’t you rather take your inspiration from Gloria Swanson?

Here she is merrily camping it up in her Manhattan apartment when she was 73. Yes, the Glamazon makeup’s a bit much… but good heavens, look at that complexion! To quote a song from the season just passed, you could even say it glows! And she still had the perfect figure for crushed velvet gowns and gold lamé pumps. Which you get the feeling she wore even when the cameras weren’t looking.

Swanson was decades ahead of the healthy-eating curve. In 1929, after producing the financially disastrous Queen Kelly, she went to her doctor complaining of stomach pains. “I thought I had ulcers because if you are a producer, you are supposed to have ulcers,” she joked. He asked for a quick inventory of what she’d been subjecting her system to—rich, gooey foods, sugary snacks, decadent cocktails—and told her to stop treating her body “like a garbage pail.” A much more obedient patient than most, she immediately swore off meat, poultry, sugar and alcohol and adhered faithfully to a macrobiotic diet.

A true evangelist, Swanson would sometimes confront people on the streets of New York—a much more dangerous move than eating sugar—and chastise them about the junk they were scarfing down at the corner hot dog stand. She even brown-bagged it to glamorous parties, where the buffet tables were groaning with deadly delicacies.

She drank only spring water from France, made her own flour from brown rice and her own sweetener from boiled organic raisins, and frequently fasted. “After one fast I was on for 10 days I swore I’d never eat again,” she said. “I was just going to eat petals of flowers…”

Okay maybe she was a little over the top.

But Swanson was right about sugar—and campaigned against chemicals and pesticides in foods before it was popular. She also created some recipes that didn’t involve making your own flour and sweeteners or eating the daisies—and I’m sure she’d forgive you if the water you use is domestic. Here’s a recipe to get your new year off to a healthy start:

GLORIA SWANSON’S POTASSIUM BROTH

8 cups spring water, bottled water or purified water

1 cup Swiss chard or kale

1 cup zucchini

1 cup fresh string beans

1 cup celery

However much or however little garlic you like

Wash all vegetables thoroughly, preferably with a veggie brush, and then chop them well. Finely mince the garlic. Pour water into a large pot and add everything. Cover and simmer about 40 minutes, or until the celery is tender. Serve immediately, or turn off the heat and allow the broth to cool on the stove, pour into covered containers and refrigerate. Reheat to serve later.

Okay, a confession: I added the garlic to Gloria’s recipe. I am a total garlic hound. When I recently ordered pasta with garlic and oil from the local pizzeria, this was my plaintive cry: “Extra garlic, please. And then if you look at it and say, whoa, that was too much garlic, just add more garlic.” (My husband was away at the time.)

In this recipe, the garlic not only adds much-needed flavor, but tons of nutrition—and packs a wallop against winter cold and flu germs. If you’re not a garlic fan, you can add any herbs (or other vegetables) you like, or perk it up with chili powder, paprika, curry powder or other spices. Take it in any direction you choose!

This is a great way to start a meal or to serve as a little something to tide you over in middle of the afternoon. And if you close your eyes and use a little imagination, it will make you feel like a movie star prepping for a glamorous role, getting ready for your close-up…

Wear the new year well, my dears!

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

TINTYPE TUESDAY: Coop, Clark, Claudette and Other Classic Stars Go Shushing Through the Snow in Sun Valley!

Happy Holidays, my dears! And welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY!

Okay, kids, pull on your best winter woolies—we’re heading to chic and trendy… Idaho! Sun Valley, to be precise. Where classic film stars showed us just how fabulous they could look in ski togs. And where some of them actually skied. No really. I have proof.

The place was something of a Hollywood concoction itself: In 1936, the owners of the Union Pacific Railroad wanted to boost traffic along some of the more remote corridors, so they hired a cash-poor Count by the name of… wait for it… Felix Schaffgtosch to scout out a place to build a glamorous ski resort. (How did no one make a movie out of this story? I see Edward Arnold and Walter Connolly as the bigwigs and Melvyn Douglas as the Count.)

Once they settled on a spot in the Sawtooth Mountains, the railroad men hired promotor Steve Hannigan, who’d helped lure the rich and famous to Miami Beach, to do the same for this snowy little speck on the map. They christened it Sun Valley to dispel fears among the hothouse flowers of Hollywood that it would be too cold to vacation there. Because, you know, if you put “sun” in the name, no one will notice the blizzards.

Imagine their suprise when some stars actually took to the wintry weather! Claudette Colbert and Gary Cooper, for instance, were regulars on the mountainside.

And shortly after filming For Whom the Bell Tolls, Cooper, his wife Rocky, and co-star Ingrid Bergman set out for the slopes with Ernest Hemingway’s brother Jack and Clark Gable. (Hemingway wrote the novel in his suite at the Sun Valley Lodge, which he called Glamour House.)

Not everyone was a natural, though, and novices like Lucille Ball and Jane Russell were happy for the help of their handsome instructors…

…while Norma Shearer married hers! Six years after losing Irving Thalberg, she wed Martin Arrouge, who had taught her and her children to ski. (And a few years later, while vacationing with her husband at a lodge in California, she discovered 18-year-old Jeanette Morrison, who became Janet Leigh.)

Sun Valley also served as the backdrop for several films, including I Met Him in Paris, How to Marry a Millionaire, The Tall Men, Bus Stop—and of course Sun Valley Serenade. And its renowned jazz festival, which still runs every year, drew the best in the business, including Louis Armstrong!

The scenery was so stunning that even Errol Flynn was lured out of the lodge when he was in town for the premiere of Santa Fe Trail.

These days, Sun Valley is still a magnet for skiers and celebrities, but of course, all the old glamour is long gone. Still, these pictures remain…

Happy trails, my friends!

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

STREAMING SATURDAY! THE HOLLY AND THE IVY Make for a Prickly Christmas

Welcome to another edition of Streaming Saturdays, where we bring you a free, fabulous movie to watch right here every week!

How can you help but love a Christmas movie where a brother and sister duck out on the family festivities to get roaring drunk?

They have their reasons. But then just about everyone has cause to knock back a few in The Holly and the Ivy, one of the least jolly Christmas movies ever. Which, for some of us, looks a lot like Christmas.

Adapted by Anatole de Grunwald from a play by Wynyard Browne (who wrote the screenplay for Hobson’s Choice), the 1952 film used to be a holiday staple on PBS back when they showed old British movies all the time. (I blame them for my insatiable crushes on Alistair Sim, Alec Guinness, James Mason, Robert Donat and Trevor Howard. They’re lucky I still give them money.) But it hasn’t turned up on TV in ages, so I hunted it down on DVD, admittedly worried it wouldn’t live up to my memories. I needn’t have feared.

In the first few scenes, which could be called “Backstory Theater,” we meet everyone who’ll be gathering for Christmas at the rambling country house of Martin Gregory (Ralph Richardson), a recently widowed vicar who’s leaning heavily on daughter Jenny (Celia Johnson) to keep his home, health and hectic schedule from falling apart. Uncle Richard (Hugh Williams) is killing a few hours in the pub before he’s due to pick up Martin’s daughter Margaret (Margaret Leighton), a fashion writer in London. But she’s taken to her bed and pulled the covers up after her, hoping to skip the whole trip. Son Mick (Denholm Elliot), who’s doing his National Service, gets busted by his Sergeant Major (William Hartnell, the original Doctor Who) for sneaking back to barracks after hours, forcing him to do some fast talking (and truth-stretching) to hang onto his holiday leave.

And Aunt Lydia (Margaret Halstan), who feared she’d be spending Christmas in her residential hotel, finally gets the letter she’s been longing for, inviting her to her brother-in-law’s house. (Halstan, with a wide-eyed gentleness that calls to mind Patricia Collinge, quietly steals away with every scene she’s in.) On the train down, she runs into Aunt Bridget (Maureen Delany), the vicar’s sister, who insists on hunkering down like a martyr in her third-class berth, balking at Lydia’s offer to pay for an upgrade. (When she gets to the house, after waiting roughly 10 seconds for someone to answer the door, she huffs, “Did you forget we were coming or what?” Does anyone not have an aunt, or God forbid a mother, like this?)

Jenny, of course, is already home—and in mortal danger of staying there. Her fiance, David Paterson (John Gregson), has just landed his dream job in Argentina, but trying to pry Jenny loose from her father may be the toughest feat of this engineer’s career. Here, as with Laura Jesson in Brief Encounter, Johnson is honor-bound to one man and in love with another. Has anyone ever made self-sacrifice so wonderfully appealing?

Eventually, after everyone’s settled in, Margaret does make it home—bucking herself up with a nip from the decanter in the hallway before facing the family. (And in the person of Leighton, she looks the way all neurotics secretly dream of looking on their best days.)

Later that night, as they’re washing up the dinner dishes, Jenny tells her sister about David and asks if she might come home for a bit to stay with their father—an idea Margaret quickly dismisses. “You say it so immediately… click, like that, it’s done with,” Jenny snaps. “Life must be very easy for people like you.” Witheringly, Margaret retorts, “Well it’s always easier than people like you make it.”

“You have grown hard, haven’t you?” says Jenny. “Mag, what’s happened to you?” And then… she finds out. Her sister has suffered an awful loss, and her grief has congealed to bitterness. Suddenly all the talk of “people like you,” on both sides, is over, probably for good.

There’s great chemistry between the gentle Johnson and the brittle Leighton, each just as vulnerable in her own way as the other. (The two were also a joy to watch, as school friends turned romantic rivals, in Noel Coward’s The Astonished Heart; much more on that fabulous film, including where to watch it, here.) During their extraordinary scene in the kitchen, Margaret says off-handedly, “What nonsense life is…” and Jenny mutters in agreement. “Do you think so?” asks Margaret, as pain and disappointment flicker ever so slightly across her face. The same stalwart quality she’d derided in her sister just a moment before is also one she depended on. In the course of a few short minutes, their relationship and their assumptions about each other have changed forever.

Meanwhile, like the doctor whose own family is wasting away in front of him, Martin is too busy tending his flock to see what’s happening under his own roof, and his children (wrongly) assume he’d disapprove if he knew. He has no idea that Margaret drinks, or why. He doesn’t know Mick is clueless about his future and Jenny is about to throw hers away for duty’s sake. In fact he’s been hoping David and Jenny would “move things along” and is thrilled about David’s new post, regaling him with tales of South America. (Oh and you really haven’t heard the word “guano” until you’ve heard it said by Ralph Richardson.)

When Mick confronts his father with the truth, he’s hurt and appalled to find out everything that’s been kept from him for so long—how his children have borne their pains alone, fearful of turning to him. It’s one of several epiphanies that unfold naturally and believably, not so much “Aha!” moments as “Ah, now I see…”

The film is not without its little flaws. Johnson, who is supposed to be 31, was 43 (and looking fabulous, but still)—a distraction that could easily have been avoided simply by not noting her age in the script. (Really, Anatole, how hard would that have been?)

And the ending felt hurried, especially since I wanted to spend a lot more time with these people. It was as if someone said, “Okay kids, we’ve only got the studio for another five minutes, let’s move it!” Some may say things are wrapped up a bit too neatly, but for me that was comforting—in the same way, I imagine, that bullied kids probably get a special thrill out of the end of A Charlie Brown Christmas. Maybe because my family is just the opposite—you hope and you pray, stupidly or crazily, that this time, people will listen and get along and understand, and then, once again, everything pretty much goes to hell. (I always carry a small dress purse to family dinners, but never too small to hold the Advil.)

But for all its minor faults, The Holly and the Ivy is quietly stunning. It sneaks up on you and stays with you, especially if your family holidays tend more toward O’Neill than O. Henry. I love these people. I love how they open their hearts and minds, toss aside their hardened beliefs about one another and start again. I love their flaws and their eccentricities, which no one holds against them. I love how their honesty isn’t edged with cruelty. I want to spend every Christmas with them.

Usually I embed Streaming Saturday movies, but this week, I’m sending you to… wait for it… a pastor! In this post, she talks briefly about the film and embeds it on the page. I have the technical skills of a backward wombat, and this was the only workable way I could find to get this movie to you!

I hope you love the film as much as I do. I send it with my warmest wishes to you and those you love, for a happy and peaceful holiday season and a wonderful new year!

STREAMING SATURDAYS is a regular feature on Sister Celluloid, bringing you a free, fabulous film every weekend! You can catch up on movies you may have missed by clicking here! And why not bookmark the page to make sure you never miss another?

From Laurel & Hardy to James Dean and Beyond: A Love Letter to George Stevens

You know how with some people, you say “I love their work!” but really, let’s face it, you’re actually in love with them?

That’s me with George Stevens. Today is his birthday, and yet it’s not even a national holiday. That’s just wrong. But we’re celebrating here at Sister Celluloid, sharing behind-the-scenes glimpses of the man at work. (And at lunch. And at chess. And at checkers. Oh and I threw in a baby picture, because look at that face!)

What does Swing Time have in common with Giant? Or The More the Merrier with The Diary of Anne Frank? Or Alice Adams with Shane? Or I Remember Mama with Gunga Din? Or Annie Oakley with A Place in the Sun? George Stevens.That’s it. Silent slapstick, rousing adventures, poignant slices of life, heartbreaking history, romantic comedies, tragic melodramas, elegant musicals, iconic westerns… there was nothing he couldn’t do and do brilliantly, with great heart.

Stevens, whose parents were popular vaudeville actors, started out with Hal Roach Studios in 1922, when he was just 17. “There were no unions, so it was possible to become an assistant cameraman if you happened to find out just when they were starting a picture,” he recalled modestly. “There was no organization—if a cameraman didn’t have an assistant, he didn’t know where to find one.”

Honing his craft on low-budget westerns, the first star he trained his camera on was Rex the Wonder Horse. But after just a couple of years, he was working as a cinematographer and gag writer for Laurel and Hardy—after rescuing Stan Laurel’s film career almost before it began. In the early 1920s, most filmmakers used orthochromatic film stock, which is mostly “blue blind,” making it impossible to capture the actor’s pale, almost luminescent eyes. Stevens had learned about panchromatic stock, which is far more color-sensitive, and tracked down a supply. And much like a silent-film hero, he saved the day.

Laurel’s daughter Lois said the young cameraman always doted on her when she visited the lot as a child. “Dad, Uncle Babe [Hardy] and George were bosom buddies,” she remembered. Stevens even shot some of her family’s home movies.

Laurel and Hardy’s comic sensibilities meshed perfectly with the humane, character-driven style of storytelling Stevens was already developing. “We did a lot of crazy things in our pictures,” Oliver Hardy once said, “but we were always real.”

“I looked at these two men and I realized that these guys understood human nature,” Stevens said of his lifelong friends. “By some artistic instinct they had this wonderful business of being in touch with the human condition.”

Less enthralled was Roach, who preferred pratfalls to personality studies. “It was the kind of comedy you see where the comedian is falling into stuff and getting up,” Stevens remembered. “It just bored me to death.” Even this early in his career—and with the Depression making jobs hard to come by—he’d give no ground on his vision: he began turning down tedious assignments and creating projects of his own. In November 1931, Roach fired him.

Which was a bit like trading Babe Ruth to the Yankees.

A former Roach stage manager recommended Stevens for a job at Universal, where he thrived until the studio ran out of money in 1933. He was soon picked up by RKO, and after the surprise success of the low-budget Laddie—a sort of rural Romeo-and-Juliet tale—he was on the studio’s radar for Katharine Hepburn’s next project. And she needed a hit. Coming off a series of flops, she’d been labeled “box office poison,” and was counting on Alice Adams, an adaptation of the popular Booth Tarkington novel, to turn things around.

Seeking a director she felt safe with, Hepburn turned to her friend George Cukor, but he was working on David Copperfield and recommended either William Wyler or Stevens. She leaned toward the more prestigious Wyler, but RKO boss Pandro Berman preferred the much cheaper Stevens—who then launched into a charm offensive of his own. Which was so effective that Hepburn was soon torn between Wyler and this new kid on the lot. Eager to get underway, Berman suggested a coin toss to settle things, and noticed she seemed a bit disappointed when it came up Wyler. So he offered to toss it again, and this time she was much happier with the outcome.

So was the studio: Alice Adams became one of RKO’s biggest hits. The film and Hepburn—who often credited Stevens with softening her brittle persona and encouraging her to show a more vulnerable side—garnered Oscar nods. “By nature she was averse to the role, but she fell in with it and loved doing it,” Stevens said of his star. “She liked the girl she became when she sat in the swing, and we explored the fact that what she was becoming in the story was really what Kate was herself. At that time she particularly liked to appear very sophisticated, yet she had a very generous heart.” (Much more on the film, and the goings-on behind the scenes, here.)

If Stevens thought his future in drama was now secure, imagine his surprise when he was next assigned a western—Annie Oakley, starring Barbara Stanwyck—followed by two Fred Astaire musicals: A Damsel in Distress and Swing Time, the dancer’s sixth pairing with Ginger Rogers and the film many consider their best. It was also Rogers’ favorite: “George gave us a certain quality, I think, that made it stand out above the others.”

With a cameraman’s keen eye, Stevens made audacious use of light and movement in the film, as some scenes almost float off the screen, even when the stars aren’t dancing. And in what became a signature strength, he somehow combined brisk pacing and snappy patter with warmth, elegance and tenderness.

Helping matters along was a Jerome Kern score with gorgeous numbers such as Pick Yourself Up, The Way You Look Tonight and Never Gonna Dance—which may be what Fred and Ginger were thinking after it took 47 takes to complete that routine. Early in the evening, Stevens—who was pretty much the opposite of a taskmaster—had suggested knocking off for the day to give the weary hoofers a break. But with “only a little bit” left to finish, Astaire insisted on continuing… until they finally wrapped at ten o’clock if you believe choreographer Hermes Pan and four in the morning if you listen to Rogers. Though both agreed that by then, her feet were bleeding.

Pan, who needed a safe, relaxed space to do his best work, loved working with Stevens, who provided a soothing counterpart to the demanding Astaire. He also credited him with helping to advance the idea of using song and dance to move the story along. (Oh and Stevens playfully cast his father, Landers, as the pompous Judge Watson, who rejects Astaire as a potential son-in-law until his financial prospects improve.)

One of the reasons a Stevens set felt so comfortable was that he did so much of the work before anyone else showed up. He often spent months on pre-production—working with writers, dreaming up sets and scouting out locations. Which sometimes led to battles with his bosses, who, for instance, wanted to film Gunga Din on a soundstage. “To make that film in a studio would have been impossible and absurd,” Stevens once said. “And despite the seventy five days in that broiling desert heat and the terrific strain on everybody concerned physically and mentally, it was worth the struggle.

“Theater audiences miss the beautiful, breathtaking scenery we were accustomed to when silent films were made on location,” he added. “In Gunga Din we reverted to the good old silent days… but I admit that often when I crawled wearily into my camp cot at night, I muttered into my beard, ‘You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!'”

The challenges Stevens faced with Woman of the Year, the first pairing of Tracy and Hepburn, were entirely different—including a script that fell about forty pages short of the finish line. But he liked what little he saw. And Hepburn, who’d been a close friend since Alice Adams, was eager for him, rather than her frequent collaborator Cukor, to direct the film. “I just thought Spencer should have a big, manly man on his team, someone who could talk about baseball,” recalled Hepburn, sounding nothing like the modern Kate we love.

As it turned out, Tracy and the openly gay Cukor, who would go on to direct the pair in Keeper of the Flame, Adam’s Rib and Pat and Mike, became good friends, while Stevens and the prickly actor didn’t hit it off at all—especially after the director inadvertently upstaged him.

“If there were only two or three people in the room, George was the funniest man you ever saw in your life,” recalled his first wife, Yvonne. “On the set, there was a [physical] bit that Spencer Tracy had to do, and Tracy didn’t quite get it, so George said ‘This is the way you do it.’ The lights went on, and George got up and did this scene, and, well, everybody just died the way he did it! So Tracy called him over and he said, ‘Don’t ever do that again.’ Because Tracy had to get up and do the same scene, and it wasn’t as funny.”

When producers Louis B. Mayer and Joe Mankiewicz decided on an ending for the film—with Hepburn botching breakfast as she strives to win over her lord and master—it was Stevens who wasn’t laughing. But both Mank and Mayer felt it was essential that Tess be taken down a peg. “Now, women could turn to their husbands and say, ‘She may know the President, but she can’t make a cup of coffee, you silly bastard!'” said Mankiewicz. (I’ll just wait here while you gag…)

Mercifully, the star of Stevens’ next two films, Jean Arthur, wasn’t taken down a single notch in either one of them. Which is the case in almost all his movies: Stevens was at least as much of a “woman’s director” as Cukor—and his strong, spirited heroines generally got to stay that way.

Shooting on The Talk of the Town started up just six weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The cast and crew hunkered down in the cozy set, relieved to be working on a breezy comedy—about an accused murderer who’s escaped from prison and a gathering lynch mob. Good times! Not surprisingly, Stevens somehow found a way to seamlessly blend comedy, politics, edgy satire and romance.

He also did something he’d never done before: shoot two endings and let preview audiences decide who wins the leading lady’s hand—in this case Ronald Colman or Cary Grant. They picked the wrong man. But some of their comments were priceless: “Colman’s beard arouses suspicions and makes him unsympathetic.” “Grant got Barbara Hutton in real life so let Colman get Arthur on the screen.” “Colman is such a well-established gracious loser. Fans enjoy seeing him suffer.”

The afterglow from The Talk of the Town carried over into The More the Merrier, maybe the best romantic comedy ever made. And Stevens, who had already decided to join the service, saw this as his fond farewell to film, unsure if he’d ever return to movies—or return at all. “You know, you might as well have some fun because you might not be around too long,” he recalled thinking at the time. (Much more on the making of the film, which I recently picked as the best movie to win over non-classic movie fans, here.)

Stevens, who called Arthur “one of the greatest comediennes the screen has ever seen,” also knew how vulnerable she was off screen. “She was interesting because she seemed to be rising above her personality,” Stevens recalled. “You had to treat her like a child when you directed her, because she was terribly anxious about everything.”

Arthur once described herself in almost exactly the same terms: “I am not an adult—that’s my explanation of myself. Except sometimes when I am working on a set, I have all the inhibitions and shyness of the bashful, backward child.” But she felt safe enough with Stevens to be playful even when the cameras weren’t rolling.

In the winter of 1942, Stevens sat alone in a darkened screening room to watch the most compelling and most appalling film he’d ever seen: Triumph of the Will, Leni Riefenstahl’s love letter to Hitler and Aryan supremacy. He said he decided to enlist that very night, to fight the evil unfolding in Europe by doing for the Allies exactly what Riefenstahl was doing for the Third Reich.

In January 1943, Stevens signed up to cover the war in Europe for the Army Signal Corps, and headed to New York for his immunization shots and a military flight to Europe the following month. But weakened by a recent appendectomy, he quickly came down with pneumonia, which was complicated by his chronic asthma. He spent almost two months in a hospital on Governor’s Island before he was deemed well enough to be released. But the illness that slowed him down also saved his life: the plane he was scheduled to be on in February had crashed, killing all on board.

By the time The More the Merrier premiered across the United States in the spring of 1943, its director was heading to North Africa.

Stevens saw himself as a propagandist for the good guys, as well as a critical liaison between those who were fighting and their loved ones waiting and worrying back home. He wrote in his diary: “Prepare the civilians by sharing the soldiers’ experiences, for resuming relationships with men who have been away… make the casualties easier to bear for those who have suffered bereavement… construct a celluloid monument for those who have been the ones to go.”

With his own 16mm camera, Stevens captured the only Allied color footage of the D-Day invasion. He was also on hand to film the gloriously exuberant liberation of Paris and the historic meeting of U.S. and Soviet forces at the Elbe River. The Library of Congress lauded his work as “an essential visual record” of the war.

After the war, Stevens was assigned to film the nightmarish conditions at the liberated Dachau and Duben concentration camps.

“After seeing the camps, I was an entirely different person,” Stevens recalled. “I know there is brutality in war, and the SS were lousy bastards, but the destruction of people like this was beyond comprehension.

“I walked into a field of people… half were dead, half were alive, and the living ones had no vitality,” he added. “In the first place we had to film it, which we did reluctantly. Strange that when you find things at their worst, the most important things to film, you can’t do it the way you should do it. The people had gotten rid of the Germans, now what are these other bastards doing sticking a camera in their face.

“I don’t know how many people were in the camp… but everybody’s lying there, pleading for water,” he recalled. “So I wonder if we can find the medics… we go bursting through the barracks and go into a room where there’s a card game going on between a German major, a German captain and two nurses. This is the medical outfit, and they said, ‘We can’t do anything, we have no people, what the hell can we do?’ I said, ‘Well, you got water. Start carrying buckets.’ So we put them all to work.”

Stevens’ footage became crucial evidence at the Nuremberg Trials and was later released in documentary form, under the titles That Justice Be Done and The Nazi Plan.

“It must have changed my outlook entirely,” he said of the war. “Films were very much less important to me.” But his films, which now took on a more serious tone, were no less important to audiences, who welcomed him back.

When he returned home, Stevens was drawn to friends who were also struggling after documenting the horrors of the war first-hand. In 1946, he joined William Wyler and Frank Capra to form one of the earliest independent production companies of the studio era, Liberty Films. It failed after just one picture, a little number called It’s a Wonderful Life. Still, well before the age of the indie filmmaker, Stevens maintained almost complete control of his movies, from the initial drafts through the final editing. “For me it’s absolutely necessary to start from the very beginning,” he once said. “I can’t think of coming and contributing something anywhere along the line other than the very start.”

“To produce and direct a movie, a man really ought to have two heads,” he added. “It’s like trying to be a traffic cop and write a poem at the same time.”

Stevens’ first post-war film was a much-needed balm for his soul. “I’d seen I Remember Mama in New York, coming out of the Army, and it was a nice little play,” he recalled. “It was set in San Francisco, and I was a kid there during that period. I knew what the city looked like, and I knew who these people were. I thought it would be fun to reconstruct it on film.

“I have real affection for that movie in certain ways, in some of the most simple ways… and I know what it meant to the audience,” he added. “It was a story of a confirmed period of the past, disassociated from all the unresolved present.”

But real life crept in soon enough: Suddenly Stevens found himself fighting a war on the homefront, when a right-wing faction of the Directors Guild of America (DGA), led by Cecil B. DeMille, tried to oust the liberal Mankiewicz as president during the height of the House Un-American Activities Committee’s communist witch hunt. In August 1950, while Mankiewicz was in Europe, DeMille mailed out “Mandatory Loyalty Oaths” for members to sign and send back, knowing it was unlikely the current president would do so.

When Mankiewicz returned, he was stunned—and found that Stevens, who called the putsch “a goddamned conspiracy,” was his only public ally on the board. But DeMille was just getting started: Next, he and his cohorts convened a secret meeting at his Paramount office, where they crafted ballots reading simply, “This is a ballot to recall Joe Mankiewicz. Sign here—Yes.” The return address was the DGA office, leading voters to believe that this was official Guild business. Oh and one more thing: to ensure a majority of favorable responses, they purged the mailing list of anyone who might be inclined to vote No—if there had even been an option to do so.

A group of 25 directors, including Mankiewicz, Stevens, Billy Wilder, Robert Wise, John Huston, Nicholas Ray, Vincente Minnelli and Fritz Lang, filed an injunction to halt the balloting, and Stevens set out to investigate the nefarious goings-on behind it. And at the next Guild meeting, he denounced the both the Loyalty Oath and the attempted recall and resigned from the board in disgust.

“George did the most incredible job of interrogation and pinning people down,” Mankiewicz recalled in A Filmmaker’s Journey, George Stevens Jr.’s superb film on his father. “He had been to the Guild office and taken testimony from secretaries and everybody… the work that George did of exposing what this was and the fact that the Guild had been run by DeMille for the benefit of a small group of men was absolutely perfect.”

Stevens later said he resented that while people like Huston, John Ford and Anatole Litvak “had served in World War II… some of those that stayed home, for whatever reasons—Ronald Reagan, John Wayne, Adolphe Menjou, and DeMille among them—had now become the judges of who were patriots or not.” He said defeating them was “the most thrilling experience. I drove 50 miles up the Ventura Freeway and back, I was so exhilarated by the victory that we’d won over the McCarthy thing.”

In the 1950s, Stevens produced what’s become known as his “American Trilogy,” starting with A Place in the Sun, which Charles Chaplin called “the greatest film ever made about America.”

Bucking the trend of the times, Stevens—who once remarked that Technicolor had an Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’ feel to it—shot A Place in the Sun in black and white. He felt color would be jarringly at odds with Theodore Dreiser’s tragic tale of a restless striver (Montgomery Clift) who falls in love with a socialite (Elizabeth Taylor) and all that her world has to offer, while growing increasingly resentful of the pregnant girl he left behind in his dreary factory town (Shelley Winters).

About the only thing Taylor and Winters had in common on the set was their affection for their director. “He didn’t make me feel like a puppet,” said Taylor. “He was an insinuating director. He gave indications of what he wanted but didn’t tell you specifically what to do or how to move. He would just say, ‘No, stop, that’s not quite right,’ and make you get it from your insides and do it again until it was the way he wanted it.”

Stevens also ran rushes for his young actors after each day’s shoot. “He would print several takes of each scene and then explain to us why one was better than the other,” recalled Winters. “The whole experience was a joy.”

Shooting from every angle was typical of Stevens, who always knew exactly what he wanted, but loved the adventure of getting there. According to his longtime cameraman William Mellor, he “probably used three times as much film as anyone else”—in this case 400,000 feet of it, which he and editor William Hornbeck worked on for more than a year. The final film earned 10 Oscar nods and six wins, including for Mellor, Hornbeck, and, at long last, Stevens.

The director was no less protective of his film more than a decade later, when in 1965 he sued to prevent NBC from airing “a distorted, truncated and segmented version” of A Place in the Sun with commercial breaks.

“I believe the film is entitled to receive, and the public to enjoy, the same integrity in its presentation which led to its original acceptance,” Stevens said when he filed the complaint. “A motion picture should be respected as being more than a tool for selling soap, toothpaste, deodorant, used cars, beer and the whole gamut of products advertised on television. The audience, too, should be respected by being presented with a film as they remember it, and for those who have not seen it, as it was intended to be seen. Anything less is a degradation of the film and its audience.”

As you’ve probably guessed from barrage of ads that barge into most films on television, Stevens’ lawsuit did not succeed.

Next in the Trilogy was Shane, the story of an aging gunfighter who helps homesteaders fend off some of the nastiest outlaws on any side of the Pecos. (I love the shot above, of Jack Palance wildly out of character, chatting with a bicycling Stevens and Joan Fontaine.) As part of his usual meticulous research, Stevens consulted with technical advisers on everything, including what people wore on special occasions (women often trotted out their wedding dresses, as Jean Arthur does) to what they ate and how they cooked it.

But his greatest obsession was that the gunfire and its devastating effects be as realistic as possible. For the cold-blooded murder of Torrey, he had Elisha Cook Jr. rigged up to an intricate block-and-pulley system, so when he was shot by Jack Wilson (Palance), his entire body would be sent flying backward into the mud. The production department asked Stevens to tone the scene down, but he refused for the very reason they wanted him to: because it was so disturbing.

Stevens believed downplaying the effects of violence “was an outrage. I wanted to show that a .45, if you pull directly in a man’s direction, you destroy an upright figure… a living being is not able to get up again, and when a man is shot a life is over.”

He used sound effects to make the same point. “In most westerns, you know, people are shooting off guns all the time so you don’t even notice it any more,” he said. “I wanted people to be really jolted out of their seats the first time Shane uses his gun… so I got a little cannon, put it right off camera, and when Alan Ladd fires his gun, I had them shoot off the cannon and it made a tremendous roar.” For other gunshots, rifles were fired into metal barrels.

When Warren Beatty wanted to achieve the same effect in Bonnie and Clyde, he consulted Stevens and copied the techniques. But when his film premiered at Cannes, only the first shot rang out loudly; the rest blended into the background. Beatty sprinted upstairs to speak to the projectionist, who told him he’d “fixed” the sound problem. “The last time I got a film that was mixed that badly,” he told him, “was Shane!”

The final film in the Trilogy was the longest of Stevens’ career: the sprawling Giant, adapted from Edna Ferber’s novel about three generations of a Texas oil family. “George Stevens takes three hours and seventeen minutes to put his story across,” wrote Bosley Crowther in The New York Times. “That’s a heap of time to go on about Texas, but Mr. Stevens has made a heap of a film, and Giant, for all its complexity, is a strong contender for the year’s top-film award.” The movie went on to earn 10 Oscar nods, but only Stevens went home with the trophy.

Leading with his heart, Stevens had originally wanted to cast his friend Alan Ladd, who was struggling to find work, in the pivotal role of Jett Rink. But Ladd, who was clearly too old for the role, was also unable to handle the physical demands of a long shoot in the blazing Texas sun. Just a few years later, Stevens would serve as a pallbearer after Ladd took his own life.

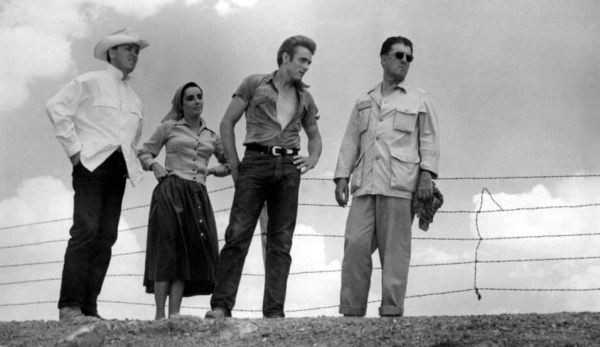

While casting for Giant was underway, James Dean was on the Warner’s lot working on Rebel Without a Cause. He was not yet the sensation he’d soon become—or even vaguely recognizable. But he’d heard about Giant from Stevens’ longtime collaborator, Fred Guiol, and he wanted in. “When we were finishing the script, this boy used to go by my office… he had to come in the back door because the girl in our office wouldn’t let him in,” Stevens remembered. “She said, ‘There’s this fellow out here, I don’t know who he is, he’s got a rope and he’s making tricks with it out there.’ Jimmy was not the man to play this part… it should have been a physically larger man… but this guy was absolutely fascinating.”

As it turned out, he and Dean fought almost constantly. Dean bristled at what he saw as suffocation, while Stevens, who favored naturalism, tried to rein in some of the young actor’s excesses. He succeeded on at least one front: during filming, he’d had forbidden Dean from so much as sitting behind the wheel of a sportscar. But in September 1955, just days after finishing his scenes and before the movie had even wrapped, Dean was killed on his way to a race in Salinas. Ironically, he wasn’t speeding, and the accident was not his fault. (Much more on Dean and the fatal crash here.)

In 1957, a year after Giant premiered, Stevens began work on a project that took more than two years to complete: The Diary of Anne Frank.

Before a script was even roughed out, he revisited the Dachau concentration camp, the memory of which had haunted him for years, as well as the Bergen-Belsen camp where Anne died. He worked closely with former members of the Dutch resistance to shape the screenplay. And he supervised the meticulous re-creation of the Amsterdam home where the family hid from the Nazis, which he visited with Anne’s father Otto, who consulted on the film.

“We went to the floor where they had the little paneled living quarters, as described in her book, and then there was a garret above that,” Stevens remembered. “And as I was walking up the ladder behind Mr. Frank, there was… this gabled window and it had blown open… and there was a pigeon, or some other large bird. We didn’t see it, but it made a great rustling of its wings and it flew out the window. And this man was a strong man, but he weakened on that ladder, you know, the sense of being there and not being seen, and being winged… and he was terribly shaken by that… as if it had been her spirit. And we sat up there in the garret for a long time… and finally when he got his breath, he said, ‘Let’s go for a canal ride and escape this, and then we’ll come back another day.'”

With the exception of the blow-ups with James Dean on Giant, you’d be hard-pressed to find much evidence of angst on a Stevens soundstage. He ran a very quiet set, giving actors the space they needed to concentrate. Even the clanks and clunks of the crew and their equipment were muffled as much as possible. “I feel that my real job as a director is to be a kind of host on the film set,” he explained. “I have to help create very tangible and convincing people on the screen, and blend that with the actors’ own interpretations of their roles, so the story is as convincing as possible.

“If an actor doesn’t need any help, don’t disturb his assurance in any way,” he added. “If an actor needs not only help but strength too, give them all of that. Give them something to stand up with, and if they are still lost, give them a concept of the role and a reading of the line. I think an actor has the right to call on a director whenever it is necessary.”

No wonder actors loved him. And so did his fellow directors. When production of The Greatest Story Ever Told became bogged down with technical problems (including a blizzard in Arizona, which prompting actor David Scheiner to quip, “I thought we were shooting Nanook of the North!”), David Lean and Jean Negulesco stepped forward to direct second units, the first time either had done so in decades.

His close friend Huston counted Stevens as one of his favorite directors, along with Wyler and Ford. “When I watch one of George’s films,” he said, “I get so caught up in the story, in the people, I forget I’m watching a movie.”

Stevens was also one of an elite handful of directors George Cukor invited to his home in November 1972, to celebrate Luis Buñuel’s birthday. (Oh and hop in the car, kids, because we are going to this party.) Standing are Robert Mulligan, Wyler, Cukor, Robert Wise, Jean-Claude Carrière, and Buñuel’s producer, Serge Silberman, and seated are Wilder, Stevens, Bunuel, Alfred Hitchcock and Rouben Mamoulian. (A frail Ford could stay only briefly.)

Before there were film snobs fawning over their auteur of the month, there was George Stevens. He fought against greedy studio bosses, political demagogues and rampant commercialism—and for artistic freedom and integrity—before it was cool. Just because it was right.

And before “outsider films” became a thing, Stevens painted unforgettable portraits of underdogs such as Alice Adams, Leopold Dilg, Shane, Jett Rink and the misbegotten George Eastman. In an era of film factories, he was a humanist.

“To the young members of the Directors Guild who were idealists and who wanted to make good films, George was a sort of Pope, or certainly a cardinal,” remembered his close friend, Fred Zinnemann. “He was one of the few people who could stand up to the front office. We all learned that we could have some measure of success if we didn’t give up. Nobody at the studios took film seriously as a creative medium. George was one of the people who instilled in the studios that film was more than that.”

So Happy Birthday, my beloved George. Thank you for everything. Every Extraordinary Thing. Here’s loupin’ at you, kid.

TINTYPE TUESDAY: HOLLYWOOD CELEBRATES THE HOLIDAYS Hits the Bookshelves!

Welcome to another edition of TINTYPE TUESDAY!

Still searching for that last-minute gift for a classic movie fan? Or maybe you’ve run your tootsies ragged and you deserve a little something yourself? Look no further than the gorgeous new book, Hollywood Celebrates the Holidays: 1920-1970!

Lovingly written and researched by film historians Karie Bible and Mary Mallory, this hardcover passport to classic movie heaven takes you through every holiday from New Year’s Day through Christmas, as only Old Hollywood could. These fabulous photos span the spectrum from naughty to nice, from high glamour to wholesome, and from holy to hilarious.

Take, for instance, the Christmas chapter. Tucked among the more heartwarming pix are W.C. Fields as Old Saint Nick, surrounded by much leggier elves than any I remember, and Peter Lorre sneaking up on a Santa-clad Sidney Greenstreet with a baseball bat. Oh and don’t look now, but Joan Crawford is perched on the chimney with a shotgun—and she doesn’t look happy. But Carole Lombard does, in one of many lovely shots beautifully reproduced in this volume. Suddenly your holiday won’t seem complete until you have a glow just like that…

Mallory and Bible, both lifelong old-movie addicts, happily plundered their own photo treasures, and then scoured auction sites, paper shows, and film archives such as the famed Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles, where you just want to hide out until closing time and wander the stacks all night long. “We were also very fortunate to have the support of some really great collectors who generously opened their vaults to us,” said Bible, who was born on Halloween, which is lavishly represented in the glossy pages of the book.

Amidst all the major holidays (and some minor ones) is a chapter on Hollywood’s all-out effort to rally the nation and sell bonds during World War II, featuring some of the same imagery you’ll find in the section devoted to Independence Day. And yes, that’s Mae West as Lady Liberty (Libertine?).

Then there are the “What were they thinking?” photos, like the one of Charlie McCarthy’s head superimposed on an actual toddler’s body, with butterfly wings attached because, hey, why not? “When I first saw it, I said ‘Wow! This is so wrong, we must include it!'” Bible laughed. If Cupid actually looked like this, we’d all be begging for the sweet mercy of solitude. Much like Dorothy Hart, who’d really like to shake the pervy bunny peering over her shoulder. “I wondered why in the world the studio would employ a life-size man in an Easter photo, especially one that objectifies her on so many levels,” mused Mallory. “How did the Production Code even approve it?”

Many of the photo captions feature the original verso text that was typed on the back by the studio publicists. (Because—duh!—these pix were, of course, promotional tools!) Ironically, the leering Easter bunny was touting one of the most innocent films ever made: “The rabbit’s visit to Hollywood served a dual purpose, as he was doing a bit of technical advising on Harvey, which will star Jimmy Stewart with an invisible rabbit.”

As of today, this fabulous book was available at some online booksellers, including Barnes & Noble, but out of stock at others, such Amazon. If you have trouble tracking it down, you can order it directly from the publisher. And really, if you’re buying it as a gift, pick one up for yourself too. Because once you peruse its pages, it’ll be awfully hard to part with!

Full disclosure: While Mary and I know each other only online, I’m lucky enough to call Karie a friend. But I bought my own book; friends don’t let friends give them free review copies! This was a labor of love for these two, who poured in tons of research hours and their own money, buying up photos and paying for publishing rights. I know there are lots of classic film writers and bloggers who scarf down every freebie in sight, but after all the time and expense the authors put into this, I would’ve felt like a heel mooching a free copy. So when I suggest you buy this book, rest assured that I bought it too!

TINTYPE TUESDAY is a weekly feature on Sister Celluloid, with fabulous classic movie pix (and usually some backstory!) to help you make it to Hump Day! For previous editions, just click here—and why not bookmark the page, to make sure you never miss a week?

Recent Comments